ENDANGERED – FAUNA AND FASHION: FUR

By Nicole Johnston and Jean Parsons

Painting, Georges Schreiber – American (1947) Museum of Art and Archaeology

September 20, 2018

The hides and skins from both wild and domesticated animals are used in the apparel industry, either with or without hair, the latter in the form of leather. A few of the more common animals used as sources of hides and skins include cows, foxes, rabbits and minks.

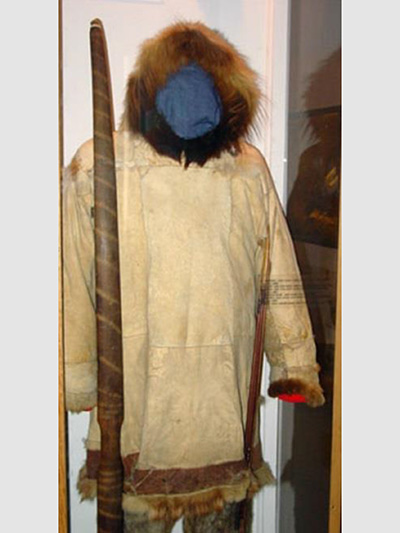

Before gaining recognition in the luxury fashion market, fur was worn for purposes of protection and for decoration. Over 5300 years ago during the late Neolithic, for example, Ӧtzi, whose mummified remains were discovered in 1991, roamed the snow-covered glaciers of South Tyrol, Italy, wearing a loincloth, leggings, tunic and hat made of sheep, goat, deer and bear sewn together with sinew.

Over time fur became a symbol of wealth and status throughout the world. During the 12th-14th centuries, certain types of fabrics, cuts of clothing, and trimmings, including fur, were restricted by social classes. For example, ermine and otter fur were made inaccessible to members of the middle and lower classes. Upper class nobles donned tunics, gowns, cloaks, hats, gloves and shoes trimmed or fully lined with fur. One 15th century men’s garment was documented as featuring over 1,000 ermine tails! Due to its popularity as a marker of status, ermines were hunted almost to the point of extinction during the 15th and 16th centuries.

Following the age of European exploration from the 15th to 17th centuries, other animals such as the beaver became additional symbols of wealth and status. Beaver fur was the height of fashion in 17th century Europe and by the mid-1600s, the demand had become so great, the animal was hunted to the point of extinction on the European continent. In search of pelt sources, France looked to new lands in the west, establishing fur trading monopolies on the North American continent in the St. Lawrence River region north of the Great Lakes. Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), the oldest company in North America, was established in 1670 and granted fur trading rights for animal pelts such as beaver, squirrel, fox, otter, and moose within a land area equaling approximately one twelfth of the Earth’s land mass. Trade goods were traded in a unit of value called “Made Beaver” (one male beaver skin collected during winter months was equivalent to one Made Beaver). The 1733 Standard of Trade at Fort Albany, one of three original HBC trading postings, showed that one beaver pelt could buy 1.5lbs of gunpowder, eight knives, one pair of breeches, or two yards of flannel.1

The abundance of native furs in central North America also greatly influenced America’s early development. Beaver fur became the cornerstone of the American economy by the mid-1800s. Increased demand for beaver felt hats and apparel trimmed with beaver fur made the city of Saint Louis, Missouri, the epicenter of the American fur trade. Traders collected thousands of animal pelts from trappers and Native American groups up and down the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers and throughout the Great Plains, before shipping them over land and water to St. Louis and on to Europe. However, overhunting was rampant and by 1840, Great Plains beavers were almost extinct. Other wild animals, such as the timber wolf, coyote, badger, raccoon, seal, otter, lynx, and bear, have been actively trapped for their hides, often excessively. The sea mink (Mustela macrodon) of northeastern North America, for example, was quickly made extinct in the last decades of the 19th century by over-hunting for its large furs. Once-abundant seal populations in parts of Canada, Greenland, and northern Europe continue to be commercially harvested, but pressure from animal rights groups has resulted in restrictions in the trade of pelts. Notably, in the U.S., trade in seal skins, along with all other marine mammal products, is banned.

Interest in fur products began to decline from the 1960s-80s through active animal rights campaigns and increased environmental awareness. Environmental movements of the period recognized that hunting, and loss of habitat through development, posed a threat to numerous animal species such as American crocodiles, cheetahs, tigers, and snow leopards, all of which had pelts or skins used for fashionable clothing and accessories These animals were considered endangered or under threat of extinction. The United States passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973 to protect such animals.

Hides and skins are often the byproduct of other industries such as meat and dairy, but may also be acquired for the sole purpose of producing luxury apparel and accessories. During the mid-19th century, mass production of animal fashion products began with fur farming as a means of guaranteeing sufficient stock for the fashion market. The term “fur farm” refers to the practice of breeding or raising certain types of animals for their fur. The majority of minks, for example, although found in the wild almost everywhere in North America, are ranched. Very few wild mink are trapped due to the preferred quality and color of genetically bred American minks, characteristics which can be guaranteed through fur farms. One mink coat may require approximately 60-80 mink skins. Today, mink and fox account for approximately 80% of farmed fur, with the remaining 20% representing a great diversity of species including rabbits, Asiatic and Finnish raccoons, and chinchillas. Sixty-four percent of fur farms can be found in northern Europe, 11% in North America and the rest dispersed throughout the world in countries such as Argentina and Russia.2

Animal rights groups actively protest the existence of fur farms, often promoting legislation to monitor fur farming activity. Most recently, in 2018 the largest animal rights organization in the world – People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) – successfully sponsored legislation in San Francisco to ban new sales of clothing items and accessories that contain real animal fur. The ban, which will take effect January 1, 2019, is hailed by some as a positive step away from animal cruelty, while others view it as hurting small businesses, particularly as sales of real animal products are forecasted to increase in 2018. Young consumers are also turning to faux fur as an alternative to the real thing. Recently, some high-end fashion labels have chosen to go “fur-free”, including Calvin Klein, Stella McCartney, Vivienne Westwood, and Tommy Hilfiger. See examples of faux fur in the IMITATION category on the Endangered: Fauna and Fashion homepage.

- Hudson’s Bay Company. Accessed June 30, 2018: http://www.hbcheritage.ca/home

- JCR-VIS Credit Rating Company Limited; October 2017. Accessed 7.9.2018: http://jcrvis.com.pk/docs/Leather%20Industry%20%20201710.pdf

Return to Endangered: Fauna and Fashion homepage

Return to Origins: Dress and Textiles homepage