ARTS AND CRAFTS DESIGN (RE) FORMS

By Nicole Johnston and Jean Parsons

June 13, 2019

Rooted in the ideals of pre-industrial times, the Arts and Crafts movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries advocated reform to improve standards of decorative design debased by mass manufacturing. Concepts of handcraftsmanship and manufacturing were re-evaluated to shape more modern forms of visual arts, home furnishings, textiles and more. Women’s roles also began to change, through increasing access to education and technical training. They engaged in professional careers as working artists, designers, and entrepreneurs.

A more modern template for clothing and accessories emerged alongside the decorative forms of Arts and Crafts, as designers within the movement incorporated handcrafted traditions, natural motifs, and historic and Eastern influences while also encouraging a less restrictive style of dress for women.

ARTS AND CRAFTS DESIGN (RE)FORMS by the Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection explores these associations in an exhibition of decorative arts and related dress of the period. Scroll below or use the following links to learn more about the founding of the Arts and Crafts movement and its basic Tenets. Decorative Forms highlights some of the major decorative and applied artistic forms and artisans of the movement. Craft of the Needle explores influences of the movement in needlework and embroidery; Dress Reform discusses associations between the Arts and Crafts movement, Artistic and Aesthetic dress, and women’s dress reform.

The MHCTC would like to thank the following individuals for their support to help make this virtual exhibition possible:

- Alex Barker, Director, Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri

- Alisa McCusker, Curator of European and American Art, Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri

- Kelli Hansen, Librarian, Special Collections and Rare Books, Ellis Library, University of Missouri

- Shelly J. Croteau, Assistant State Archivist, Missouri State Archives

- Harrison Sweazea, Missouri Senate Photographer

- Tiffany Patterson, Director, Missouri State Museum, Jefferson City, Missouri

- Elyse Zorn Karlin, Author: Jewelry & Metalwork in the Arts & Crafts Tradition; Publisher and Editor-in-Chief: Adornment: The Magazine of Jewelry and Related Arts

EXHIBITION OPENING RECEPTION An opening reception for the summer exhibition was held on June 20th that included additional dress and archival objects on display, including hand-blocked books from 1892 and 1900 printed at Kelmscott Press and Roycroft Press. Several guests tried their hand at embroidery using stencils created from textile objects in the exhibition. The MHCTC would like to thank TAM PhD student Lida Aflatoony for demonstrating period embroidery techniques and Kelli Hansen from Special Collections and Rare Books for sharing her knowledge of Arts and Crafts printing. The exhibit’s website was also accessible during the event for guests to explore.

THE ARTS AND CRAFTS MOVEMENT

In the mid and late 19th century changes emerged in the value society placed on how things were made. As the industrial revolution swept through England and America, thousands of workers were needed for factory jobs and it was no longer practical to spend years working to learn a skilled trade in the apprenticeship system that had previously existed for centuries. Emphasis was placed on speed of production for greater profit, and craftsmanship was replaced by machines. This led to a decline not only in the quality of products but also the quality of life for the worker.

An Arts and Crafts philosophy soon developed among British intellects such as Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) and John Ruskin (1819-1900) as a reaction to the industrial revolution and its machines, which they argued dehumanized the worker and divorced him from nature. As one of the period’s leading art critics, Ruskin emphasized intersections among nature, art, and society and wrote extensively about the connections between the social role of art and the value of work. In Modern Painters (1843) Ruskin argued that the principal role of the artist is “truth to nature,” meaning “moral as well as material truth”34.

As part of this new philosophy, concepts of handcraftsmanship and manufacturing were re-evaluated in reaction to the damaging effects of machine-dominated production on both social conditions and the quality of manufactured goods, including the decorative arts. The Arts and Crafts movement of the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries advocated reform to improve the standards and status of decorative design. The Movement took its name from the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, a group founded in London in 1887 with the chief aim of raising the social and intellectual status of crafts. The Society’s first president was the artist and illustrator Walter Crane (1845-1915) who viewed art as a tool to transform society. In his influential book, The Claims of Decorative Art (1892) Crane argued that art, especially the crafts, would flourish in a socialist society once an individual was freed from the “bounds of wage slavery” that existed within the capitalist system and he could then devote himself to artistic pursuits.22

“Machinery can never supersede the craftsman’s hand in producing work which is to have a distinctive character and value of its own and that the methods of the factory system are fatal not only to the artistic quality of the things made, but also the mental and physical well-being of the workers employed.”

– Haslemere Peasant Arts Society, 1894

Walter Crane was a close friend of fellow socialist and artist William Morris (1834-1896) whose teachings also made associations between art and labor. A figurehead of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Morris argued for the return of small-scale workshops to create beautiful, well-made applied-art objects for use in everyday life. In his 1881 lecture Art and the Beauty of the Earth, Morris postulated that machines can do everything “except make works of art”23.

Morris’s instinct for decorative beauty in surface ornamentation emerged in a variety of forms including print, metalwork, dyeing, and weaving. His printing company, Kelmscott Press, printed lavish, decorative volumes of texts designed as art objects to be experienced as much as books to be read. In 1861 Morris partnered with friends to found the manufacturing and decorating firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co (later Morris & Co.) with a structure based on the concept of medieval guilds in which craftsmen both designed and executed the work. His ideal was further strengthened by his friendships with members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who also took inspiration from both nature and medieval culture. Brotherhood members such as Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) were committed to the concept of naturalism and applied this concept not only to representations of the natural human form in art but also to how the human body should be adorned in styles that highlight a natural form.

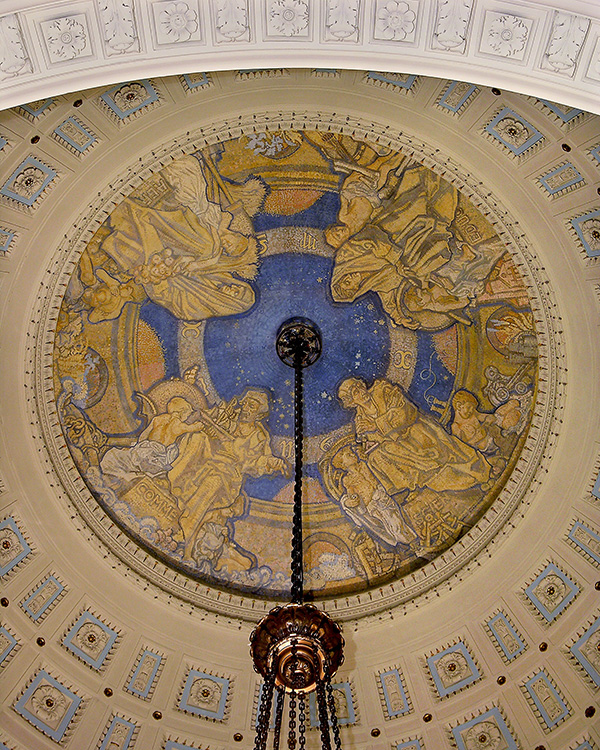

Sir Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) worked briefly as an apprentice for Morris’s workshop and believed, as did Morris, that art should be as widely available as possible, or at least “within reach of discriminating persons of moderate means,” rather than restricted to a wealthy elite.50 As befitting his Arts and Crafts background, Brangwyn believed an artist’s mission was “to decorate life”50. He was also highly regarded in European artistic avant-garde circles. As an internationally renowned artist-craftsman, Brangwyn created over 12,000 designs and works in the forms of murals, oil and water color paintings, ceramics, textiles, tapestries, carpets, posters, stained glass, wood engravings, and prints. Many of these designs were rooted in the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement: honest design enhanced by quality craftsmanship and appropriate materials.50 Trips to Morocco, Belgium, Romania, South Africa, and the Mediterranean also highly influenced Brangwyn’s work. His Mediterranean travels, in particular, resulted in experiments of color evident in prestigious commissions for Louis Comfort Tiffany and the Rockefeller Center in New York. Color is also a key element of Brangwyn’s 1917 commission for the Missouri State Capitol building in Jefferson City. Thirteen murals were created for the rotunda of the newly constructed state house (see image below.) “The form of decoration which has occurred to me is something very light and pure in color. That is why I have used a color scheme of bright blue and gold with splashes of deep rich orange”49. Today, the William Morris Gallery holds the second largest collection of Brangwyn’s work in England, after the British Museum.50

Aspects of the principle of “truth to nature,” meaning “moral as well as material truth” (Ruskin) and other principles of the Arts and Crafts movement fostered progressive new art schools and technical colleges that encouraged the development of both workshops and individual makers, as well as the revival of traditional handcrafts. Ruskin’s teachings influenced not only Arts and Crafts practitioners like William Morris but also those of Art Nouveau in Europe (1890-1905), Walter Gropius (1883-1969) and his Bauhaus Design School in Germany, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) and the Glasgow Government School of Design (now the Glasgow School of Art) in Scotland. Design principles of the Arts and Crafts Movement became a catalyst for Modernism, influencing design from the mid nineteenth century to the late twentieth century.

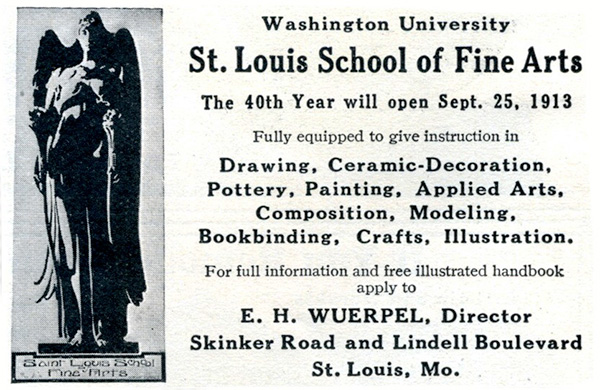

Exhibition was a key component of the Arts and Crafts movement. Hailed as a milestone in its history, the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, held in St. Louis, Missouri, was influential in the organizers decision to exhibit carefully selected examples of the applied arts alongside the traditional high arts. This pioneering emphasis on the equality of the arts lent credence to the contemporary Arts and Crafts and Design Reform movements and was crucial to their diffusion. In 1906 the Palace of Fine Arts building, constructed for the fair, became home to Washington University’s St. Louis School and Museum of Fine Arts, a collection formed in part to acquire significant works by artists of the period.54 Founded in 1857 Washington University’s School of Art and Design was the first professional, university-affiliated art school in the United States.52 In 1881 a new building was created as an independent school and named the St. Louis School and Museum of Fine Arts which was rededicated in 1906 as the St. Louis Museum of Fine Arts upon its relocation to the Palace of Fine Arts building. In 1909 the museum detached from Washington University and is now the public Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM) in Forest Park.51

Gustav Stickley (1858-1942), one of the most highly influential American artists of the Arts and Crafts movement, selected Washington University’s School of Fine Arts for his ‘Blue List of Schools’ in the October 1913 edition of his magazine The Craftsman. The School offered a variety of coursework in applied arts, pottery, bookbinding, crafts and more. Now part of the Sam Fox School of Visual Art and Design, it is the only art school to have fathered a major metropolitan art museum.52

22 Crane, Walter. The Claims of Decorative Arts. London: Lawrence and Bullen. 1892. https://archive.org/details/claimsofdecorati00cran/page/n4

23 Morris, William. Art and the Beauty of the Earth. London: Longmans & Co. 1898. https://archive.org/details/artbeautyofearth00morr

34 “The Works of John Ruskin. Cook, E.T. and Wedderburn, A.,eds. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co. 1903. Retrieved June 2019.

49 Complete Report of the Capitol Decoration Commission 1917-1928. Pickard, John, president. (1928).

50 “Frank Brangwyn: an introduction.” https://www.wmgallery.org.uk/collection/frank-brangwyn-an-introduction Retrieved June 2019.

51 https://libguides.wustl.edu/universityarchives/fine-arts-school Retrieved June 2019.

52 https://samfoxschool.wustl.edu/about/history Retrieved June 2019.

53 Stickley, Gustav. “The Craftsman Movement.” The Craftsman Magazine Vol 25 No 1 (October 1913): 18-26. The Craftsman Publishing Co., New York City.

54 http://greatriverroad.com/stlouis/kemper.htm Retrieved June 2019.