ENDANGERED – FAUNA AND FASHION: SHELL, BONE, HORN, TEETH, ORGAN, EXTRACTS

By Nicole Johnston and Jean Parsons

September 20, 2018

A variety of animal products beyond fur, leather and hair are utilized in the fashion industry. Animal bone, shell, and teeth were some of the earliest forms of animal adornment worn by humankind. Additional sources of raw materials utilized for apparel include animal organs, extracts and quills. Many of these animal products are still utilized – and often exploited – today.

Tortoises and marine turtles are examples of animals that have been exploited to the point of endangerment. The U.S. Marine Turtle Protection Act states it is illegal to sell endangered or threatened sea turtles. Marine turtles, their nests, eggs and habitats are also protected under the Federal Endangered Species Act of 1973. Despite legal protection, marine turtles remain prime targets for wildlife traffickers. Hawksbill sea turtles, for example, face a myriad of threats from human activities despite protections afforded by CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, as early as 1977. In the past century global hawksbill populations have declined by a staggering 90% as a result of the demand for their shells.¹ Products made of sea turtle shell, commonly referred to as tortoiseshell, range from medicinal supplies to fashion accessories, even instruments and wall hangings. In Japan where hawksbill shell, or bekko, has been used for over 300 years, combs of bekko shell remain an important part of traditional Japanese wedding dress. Sea turtles like the Olive may also be killed for their skins to make leather products. Sea turtle meat and eggs are also harvested for human consumption or for ceremonial purposes.

Mollusks are another species of marine animal whose shells are used as raw materials in dress. Conch shells, a term generally applied to large snails whose shell comes to a notable point at both ends with a high spire, are used in fashion as jewelry, beads, buttons, and more. Conch is considered endangered and closely regulated in certain areas of the world. CITES also governs the international trade in mother of pearl, or nacre, produced by a variety of mollusks. The outer layer of pearls and the inside layer of the pearl oyster, freshwater pearl mussel, and abalone shells are made of nacre. Until the 1930s, Muscatine, Iowa was a center for pearl button production, harvesting mussels from the Mississippi River. As mussel populations began to decline, much of the production moved to Japan and now most comes from China. Other uses for nacre include buckles, jewelry and handbag frames, as well as decoration on musical instruments, knives, guns, home furnishings, and architecture.

Shell products used in apparel are often byproducts of the food industry. However, some marine animals are harvested just for their shells, often for sale to the tourist trade. The international shell trade has devastating consequences to ocean ecosystems and their inhabitants. Large-scale commercial collection also damages marine habitats such as coral reefs and sea grass beds. Only a few species, notably the queen conch, the chambered nautilus, the giant clam, and some snails are protected under CITES.

Commercially exploited for centuries worldwide, precious corals have been used as amulets or jewelry since antiquity and more recently as supplies for aquarium and zoo exhibits. Rising water temperatures and increasing ocean acidification have also caused stress to coral reef habitats.²

Certain mollusks have also been used throughout history as dyes for textiles. Tyrian purple, a natural crimson or purple dye, was one of the earliest forms of animal dyes. The glandular mucus of certain mollusks known today as Bolinus brandaris provided a variety of purple hues. “Milking” or crushing approximately 8,000 snails produced only a single gram of pure, colorfast dye which made Tyrian purple a mark of prestige. In ancient Rome, it became the color of royalty, and an item of luxury trade.

Other natural purple and red dyes were created from insects such as kermes and cochineal beetles. The cochineal beetle, a small parasite that feeds on the prickly pear cactus, was cultivated domestically in Mexico and Peru in pre-Hispanic times prior to its introduction to Europe in the 16th century where it remained in popular demand for more than three centuries. Because cochineal was the source of a more intense and lasting red than many other pigments then available, demand soared for it as a dye for European silks, velvets and tapestries until it became second only to silver as the most valuable export from Spain’s American colonies. These natural red dyes were not very permanent, however, and more colorfast, less expensive alternatives were sought. The world market for cochineal dye plummeted after German chemists C. Graebe and C. Liebermann developed alizarin crimson in 1868 while searching for a synthetic alternative to the natural red dye derived from madder plant (Rubia tinctorum) root extract. Today, the majority of all dyes used in the apparel industry are synthetic.

In addition to shell, other animal substances such as teeth and bone were used as adornment by early humankind and continue to be used in a wide variety of applications. Teeth were drilled and used as decoration on clothing and jewelry. Sharks commonly lose teeth and replace them over their lifetime, so many are found, rather than killing a shark. The shark tooth was recognized by early Hawaiian inhabitants as symbols of protection, as well as by nobility during the Renaissance. Shark teeth were also commonly used as tools and weapons by many early indigenous populations. During the 1800s whale teeth acted as a substitute for elephant ivory in products such as the handles of walking sticks, chess pieces, and piano keys. Smaller amounts of noncommercial ivory are obtained from the teeth of wild and domestic pigs and boars, beaver, elk, camel, and bears. Main sources of commercial ivory are provided by elephants, walrus, whales, hippopotami, and warthogs.

Early humankind used animal bones as tools, musical instruments, and decoration. Antlers and long bone fragments were frequently shaped into such items as arrow and spear points or needles and awls to join together animal skins. Later civilizations fashioned hair combs, hair pins and pendants from this natural substance. Small, slender fibulae bones of birds were used as stick pins to join wraps of animal skins and later woven and knitted textiles.

Although not actual bone, “whale bone”, or the baleen fronds of whales, was utilized for centuries in women’s fashion. This keratinous material, found in the upper jaws of baleen whales, was cut into narrow strips and inserted into the lining of fitted styles of outer garments and in corsets, as well as hoop skirts and stays for collars. It also made a lightweight yet sound frame for umbrellas. Populations of right, grey and bowhead whales were hunted for their baleen and oil, the latter of which was used to make candles, lubrication, soaps, paint, varnish, and some textiles and ropes. Overhunting meant whales could no longer be harvested on a commercial scale. Today, baleen whales continue to be harvested but in the United States, “baleen products may only be legally sold by Alaska Natives as Traditional Native Handicraft under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act. The baleen must be cleaned and polished to qualify as handicraft. Once purchased, bowhead baleen may be transported out of State, but may not be subsequently sold or taken outside of the United States.”3

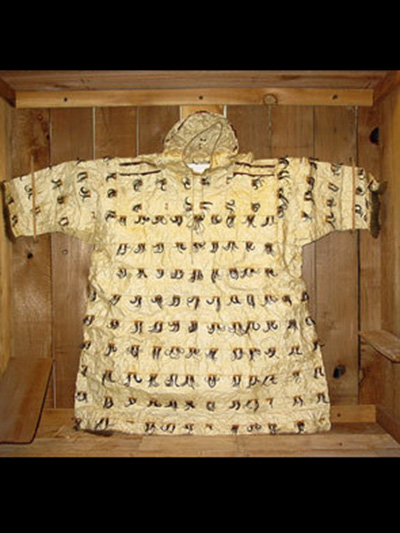

Northern native populations also utilize other, more unique, animal substances as elements of clothing and accessories. Intestines of sea mammals are worn by Inuit men and women over other clothes for protection against sea spray or sleet, and for ceremonial purposes. Parkas are created from strips of intestine sewn together and decorated with a variety of other animal products such as mandibles and feathers. The bladder, stomach or pericardium (double-walled sac containing the heart) of animals have also been used as small pouches to hold various objects and to gather, transport, and store game and other food.5

- Marine Turtle Protection, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Accessed July 7, 2018: http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/managed/sea-turtles/protection/

- Tsounis, G. S. Rossi, R. Grigg, G. Santangelo, L. Bramanti, and J. Gili. “The exploitation and conservation of precious corals.” Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review. Gibson, R.N., R.J.A. Atkinson, and J.D.M. Gordon, Editors. 2020, 48, 161-212.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Laws and Regulations; https://alaskafisheries.noaa.gov/pr/buying-marine-mammal-products

- White, James, Ed. Handbook of Indians of Canada. Published as an Appendix to the Tenth Report of the Geographic Board of Canada, Ottawa, 1913, 632p, pp. 54-55.