FLORA AND FASHION: LEAF FIBERS: PINEAPPLE, SISAL, PALM, ABACA

By Nicole Johnston and Jean Parsons

September 20, 2018

Leaf fibers are obtained from the leaves of plants such as pineapples, bananas, and sisal. Most are long and fairly stiff and do not dye easily.(2) Piña fabric derives from the pineapple leaf, specifically those of the native Philippine red pineapple. In the Philippines, piña production dates back to the sixteenth century.(13) Today, piña cloth is part of the Filipino national costume, used for formal and wedding attire. Piña is also used to make mats, bags, and table linens. Acquiring the lustrous fiber is labor intensive in that the leaves are first harvested and any thorns are removed by hand. “The top layer of the leaf is then scraped away to uncover bastos, a course fiber used to make twine. After the bastos is removed, the leaf is scraped again to reveal and extract the finer, inner fibers called linawan which is washed, whitened, and dried. Individual fibers are knotted together by hand and spun into spools to be woven into piña cloth. The cloth can then be decorated with a traditional style of hand-embroidery called calado.”(13) See an example of embroidered piña cloth in the men’s barong below. Traditional piña cloth is considered very sustainable as the leaves used to make piña are an agricultural waste product of pineapple harvesting; no additional water, fertilizer, etcetera is needed to make the fabric. Piña threads typically require no chemical refining and are biodegradable.

SISAL (Agave sisalana) is a species of agave native to southern Mexico that yields a stiff fiber used in making products such as rope and twine, as well as paper, hats, bags, footwear, wall coverings, and more. Over a 7-10 year period, the sisal plant typically produces 200-250 commercially usable leaves, each of which contain around 1,000 fibers.(10) In a process known as decertification, sisal leaves are crushed, beaten, brushed, and washed to separate fibers from the pulp.

“Sisal is a renewable resource par excellence and can form part of the overall solution to climate change. Sisal absorbs more carbon dioxide that it produces. During processing, it generates mainly organic wastes and leaf residues that can be used to generate bioenergy… at the end of its life cycle, sisal is 100 percent biodegradable.”

– Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2019)(25)

The extremely lengthy leaves of PALM and GRASSES are used in all areas of the world to make apparel, accessories, household textiles, rope, baskets, floor and wall coverings, and stuffing for furniture and mattresses. (15) The process of acquiring fibers from leaves and stalks can often be labor-intensive as much of it is done by hand. Some of the oldest apparel items in the northern hemisphere are grass shoes found in Arnold’s Research Cave in Callaway County, Missouri (see below.) In the collection of the Museum of Anthropology at the University of Missouri, the shoes date to about 6,300 BC and 2535-2390 BC and are made of Rattlesnake Master, a plant that still grows in Missouri today.

Kuba tribes in The Congos make raffia and kuba cloth from palm fibers. Traditionally, men are responsible for raffia palm cultivation and weaving. Women then pound the woven cloth to soften it and prepare it for additional surface decoration such as cut pile designs, embroidered appliqué and patchwork. Earth tones may be added using vegetable and tree dyes. Raffia cloth can be transformed into household textiles, ceremonial skirts, birth and funerary regalia, headdress, basketry, and more. Kuba embroiders today also utilize resist-and tie-dying techniques with indigo and tukula, a red powder from the hard camwood tree, to experiment with the traditional lexicon of patterns and geometric shapes. Kuba textiles made their way from the Congo to the West during the 19th century by way of missionaries and European explorers mining for ivory and rubber.(35) Several found their way into the collections of Western museums and served as design inspiration.

ABACA (Musa textilis) is a close relative of the banana and is the major fiber produced in the Philippines.(21) The course fiber is traditionally used as cordage due to its high tensile strength. Harvesting abaca is very labor-intensive as each stalk is cut into strips which are scraped, usually by hand, to remove the pulp. The long, white fibers are then washed, dried and baled. Abaca can assist with erosion control and abaca waste materials are used as organic fertilizer.(26) Water resistance properties also make abaca fabric ideal for raincoats and outerwear.

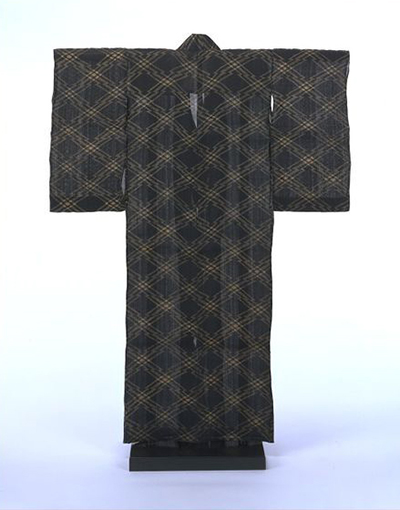

In Cambodia, abaca fibers are refined using traditional weaving techniques to create a fabric that is soft as organza silk.(11) In Okinawa, Japan, fibers from the ito basho banana plant are used in a weaving craft known as bashó-fu, designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property in 1974. Basho plants are stripped and sterilized to soften fibers which are then extracted and woven into fabric that is light-weight, strong and smooth. Approximately forty trees are required to make a standard roll of fabric. Basho-fu has been used for centuries as fabric in summer kimonos like the one below because of its lightweight characteristics.(12)

SOURCES

(2) Kadolph, Sara J. Textiles, 10th Edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc. 2007.

(10) Sisal. International Natural Fiber Organization. http://naturalfibersinfo.org/?page_id=86. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

(11) https://samatoa.lotus-flower-fabric.com/eco-textile-mill/abaca-banana-fabric/?v=7516fd43adaa

(12) “Ryuku and Ainu Textiles.” Kyoto National Museum. https://www.kyohaku.go.jp/eng/dictio/senshoku/ryui.html. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

(13) “The Queen of Philippine Fabrics: A Glimpse into the Production of Piña, a Pineapple-Based Fiber.” Student Environmental Resource Center,

University of California Berkeley. https://serc.berkeley.edu/the-queen-of-philippine-fabrics-a-glimpse-into-the-production-of-pina-a-pineapple-based-fiber/ Retrieved June 2019.

(15) Dransfield, J. 2002. General Introduction to Rattan – The Biological Background to Exploitation and the History of Rattan Research. http://www.fao.org/3/y2783e/y2783e06.htm#P889_66944.

(21) Abaca. International Natural Fiber Organization. http://naturalfibersinfo.org/?page_id=83. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

(25) Future Fibres. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/economic/futurefibres/fibres/sisal/en/. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

(26) Future Fibres. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/economic/futurefibres/fibres/abaca0/en/. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

(35) Beckenstein, Joyce. “Out of Africa, Kuba Fabrics That Dazzle and Teach.” The New York Times. April 18, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/19/nyregion/out-of-africa-kuba-fabrics-that-dazzle-and-teach.html. Retrieved 9.9.2015.

Return to Origins: Flora and Fashion homepage

Return to Origins: Dress and Textiles homepage