DRESSED TO IMPRESS: COSTUME

“I can never emphasize enough how important clothing was to me.”

– Ginger Rogers

FASHION AND PERFORMANCE

The importance of fashion to Ginger Rogers’s success as a performer cannot be understated. In fact, Rogers herself quoted in her autobiography, “I can never emphasize enough how important clothing was to me.” Costume selections for her Hollywood films became legendary. Many of them, and the dance numbers in which they appeared, later influenced many of Rogers’ costume and performance choices in her solo career. Rogers’ fashion selections not only impacted her success as a performer, but also many of the performances themselves. The weight and shapes of her garments required stamina and a unique sense of self-awareness in order to accommodate excess and often heavy fabrics, as well an eye for how the garments appeared on stage and television. The exhibition “Ginger Rogers: Dressed to Impress” explores a variety of Rogers’ past costume selections and their role in creating the glamorous persona we know as “Ginger Rogers.”

All of Ginger Rogers’ clothing on exhibit was gifted to the Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection (MHCTC) in the Department of Textile and Apparel Management (TAM) by two individuals: Roberta Olden, Rogers’ personal assistant from 1977 to 1991, and Marge Padgitt, founder of the Owens-Rogers House Museum in Rogers’ birth home in Independence, Missouri. As the steward of much of Rogers’ costume and clothing, Olden selected the MHCTC as the permanent home for garments carefully curated over the last two years from Rogers’ nightclub revue and stage career. In 2021, Olden was referred to the MHCTC by Marge Padgitt who also gifted a variety of clothing, magazines and other media from her own curated collection. These gifts became an opportunity to introduce Rogers’ iconic fashion and talent to a younger generation of college students and showcase the University’s unique research opportunities and creative design scholarship to broader national and international audiences.

Click the images below to learn more about each of Ginger’s garments! Continue scrolling to learn more about Ginger’s use of costume to craft her unique persona!

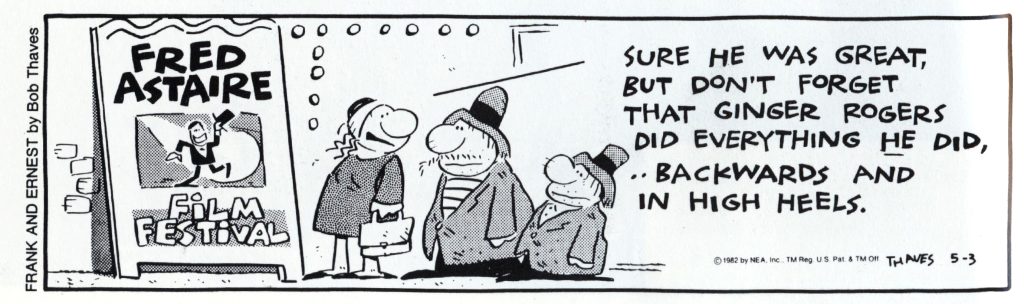

Many today are familiar with the phrase, “Sure he [Fred Astaire] was great, but don’t forget that Ginger Rogers did everything he did…backwards and in high heels.” This quote, depicted in Bob Thaves’ 1982 ‘Frank and Ernest’ comic strip, references the ten iconic dance performances of the legendary Hollywood duo Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in the early twentieth century, specifically the more challenging elements of dance – reversed footwork, high kicks, bounding leaps, and hopping turns – experienced by Fred’s dance partner, Missouri native Ginger Rogers – all in teetering heels and complex costume.

Many of both younger and older generations today are frequently unaware, however, of Rogers’ varied, strenuous – and stylish – solo career beyond her collaborations with Astaire. Ginger Rogers maintained one of the longest successful careers in Hollywood spanning over six decades from the 1920s to 1984. Rogers, with the help of her mother and manager Lela Rogers, made a successful transition from films to television, and found equal acclaim in big Broadway musicals. Her filmography of the period from 1940 to 1984 included 31 film and radio performances, one of which resulted in an Academy Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role, 18 stage appearances, several magazine features, innumerable television appearances, a jazz album, and an autobiography. Rogers’ successful and stylish solo career featured one-of-a-kind costumes, many inspired by those from her earlier career. The solo career of American icon Ginger Rogers has not received similar individual public attention in over a decade, her personal costume, even less so.

The worlds of fashion and performance costume have tended to be understood and analysed as separate and distinctly different disciplines in terms of design process and intention. While both contexts involve clothing and varied elements of performance, fashion is more commonly understood to be current, or contemporary, and based on change due to cultural factors such as social structure, technology, politics, aesthetics, economics, etc., while costume is used to temporarily communicate moods, character traits, themes, historical eras, and locations for distinct performative purposes. A costume design is produced for a designated performance with a set and character; the selected clothes and color convey information about that character – personality, age, status, occupation, nationality, mood. Furthermore, a costume must ‘read’ well from the front to the back of the performance venue and, more importantly, it must support the movement of the performer and be well constructed to survive the strains of performance.

IMAGE: Ginger Rogers as Dolly Lev in “Hello, Dolly!” (1965-67)

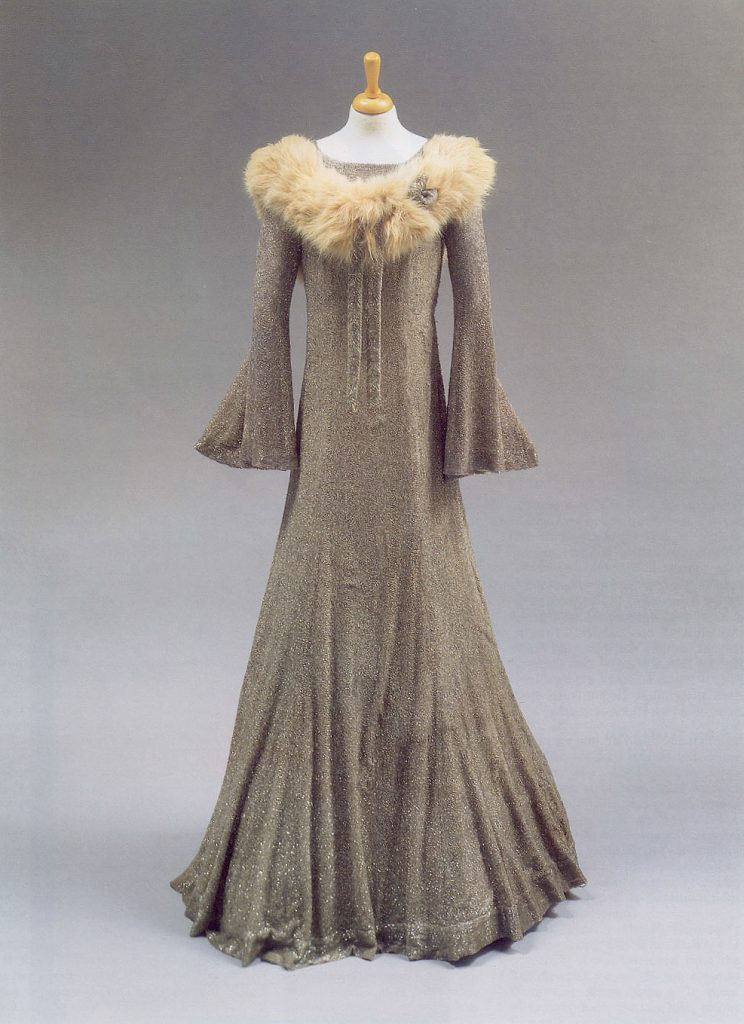

The weight, material and shapes of Rogers’ costumes required agility, stamina and a sense of form and movement, as well an understanding of how the garments were perceived by her viewers. Rogers developed these skills early in her career. For example, in “Follow the Fleet” from 1936, Rogers wore a heavily beaded blue silk dress designed by Bernard Newman for the “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” number. The costume weighed almost twenty-five pounds with wide sleeves and a collar of fur around the face. It was so heavy, Rogers had to learn to steel herself against the “onslaught of the “third person” in their routine: her dress.” Despite the frustration experienced by her partner, Fred Astaire, Rogers insisted on wearing the garment which became a hit with audiences. This was one of the costume and choreography situations from which Rogers developed her understanding of the relationships between costume and performance.

“Ginger came up with a beaded gown which was surely designed for anything but dancing. When Ginger did a quick turn, the sleeves, which must have weighed a few pounds each, would fly – necessitating a quick dodge by me. If I didn’t duck, I’d get the sleeve in the face. After a few rehearsals with this creation, I thought I had mastered the menace. When shooting of the number started, things went smoothly in the first take for about fifteen seconds. Then Ginger gave out with some special kind of a twist, and I got the flying sleeve smack on the jaw and partly in the eye. I kept on dancing, although somewhat maimed.”

– Fred Astaire, “Steps in Time: An Autobiography” (1959)

IMAGE: Ginger Rogers Beaded Dress for “Follow the Fleet” (1936) by Bernard Newman; National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institute

During her partnership with Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers developed a unique relationship with RKO Studios Head Designer Bernard Newman, a relationship that was special and collaborative. Newman, whose career was also long and fruitful, dressed Rogers more than any other actress during his Hollywood career, at a time when she was an enormous box office draw. She was considered a trendsetter; in 1938, “Life” magazine described her as “the best dressed girl in the land.” Rogers’ opinion was important to Newman as she was also the expert for what worked on the dance floor. Together, the two fleshed out Rogers’ ideas for each film, incorporating her 5’5” figure with chest-waist-hip measurements of 34”-24”-35”. Dresses were fit to Rogers’ figure by Newman’s cutter Marie Ree and built for movement. In her autobiography, Rogers recalled that Newman would sit down with her to discuss what she would be wearing in the film and show her fabric swatches. Newman also draped material directly on the actress herself, an unusual preference in Hollywood, rather than sketch a design to be created by studio seamstresses. Despite lengthy and tiring draping sessions, this attention to the star resulted in a garment with impeccable fit.

Bernard Newman was a vital part of the successful chemistry between Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. The duo represented unattainable perfection, a magic in which Newman’s designs played an integral role in enhancing Rogers’ fluid grace. Newman’s designs were an essential element of the Astaire-Rogers film series. One fan even wrote “An Open Letter to Ginger Rogers” in 1935 after Rogers expressed her desire to be known as more than Fred Astaire’s dancing partner. She implored, “Wait a while. Wait until you can’t keep up with Astaire’s more intricate steps; until you can’t quite muster the moral courage to wear Mr. Newman’s crazy creations. Then’s the time for you to “graduate” from Ginger to Madame Rogers.”

“Wait a while. Wait until you can’t keep up with Astaire’s more intricate steps; until you can’t quite muster the moral courage to wear Mr. Newman’s crazy creations. Then’s the time for you to “graduate” from Ginger to Madame Rogers.“

– “An Open Letter to Ginger Rogers,” reprinted from The Friends of Ginger Rogers Society.

Volume 2. Number 4, (August-October 1998), 21.

GINGER ROGERS: THE INFLUENCE OF COSTUME IN EARLY FILMS

In the 1930s, 40s and 50s, both men and women were drawn to movies partly by the luxury they saw on screen. As Jeanine Basinger wrote, “Fashion and glamour were direct connections to the audience’s need to see things they could never have and to experience feelings absent from their daily lives.” This was the influential power of film costume, a factor clearly understood by Rogers who stated in her 1991 autobiography, “I can never emphasize enough how important clothing was to me.” For Rogers, costume was critical: critical to making performance and critical to spectatorship. Rogers recognized from a young age the role of clothing as part of a complex performative dynamic: it is in the context of the performing body that ideas are experienced, communicated and understood.

It is the viewers’ understanding of the clothed and communicating body and their own memories and experiences that enable them to engage and connect with the ideas and narratives revealed. Award-winning Hollywood designer Edith Head described Rogers as “such a definite personality that, although she can convincingly assume the role of child or of sophisticate, the strong personality is always Ginger. No matter how you dress her, the clothes get the stamp of her individuality. She doesn’t really put on a costume as an actress would, but as a girl getting ready for a high school prom, wanting her dress to be prettiest. It’s a game of make believe… Ginger never will grow old; she has some element of clear spring in her chemistry. With one of the best figures in Hollywood, she can and does wear the beaded ball gown, but she loves the gingham dress.” Rogers understood the importance of this costume dynamic and assisted with the design of many of her film costumes.

“[Ginger Rogers was] such a definite personality that, although she can convincingly assume the role of child or of sophisticate, the strong personality is always Ginger. No matter how you dress her, the clothes get the stamp of her individuality. She doesn’t really put on a costume as an actress would, but as a girl getting ready for a high school prom, wanting her dress to be prettiest. It’s a game of make believe… Ginger never will grow old; she has some element of clear spring in her chemistry. With one of the best figures in Hollywood, she can and does wear the beaded ball gown, but she loves the gingham dress.”

–Edith Head, “The Dress Doctor,” 1959

FANTASY TO REALITY

To make their fantasies more real, viewers tried to recreate what they saw and heard at the movies, duplicating the fashion and hairstyles they saw.

- Feather sales skyrocketed “up to 85 percent” when Ginger Rogers wore a blue feather dress in the 1935 film “Top Hat.”

- It was possible to form hair braids like Rogers in “The Major and the Minor” (1942) or “Tender Comrade” (1943)

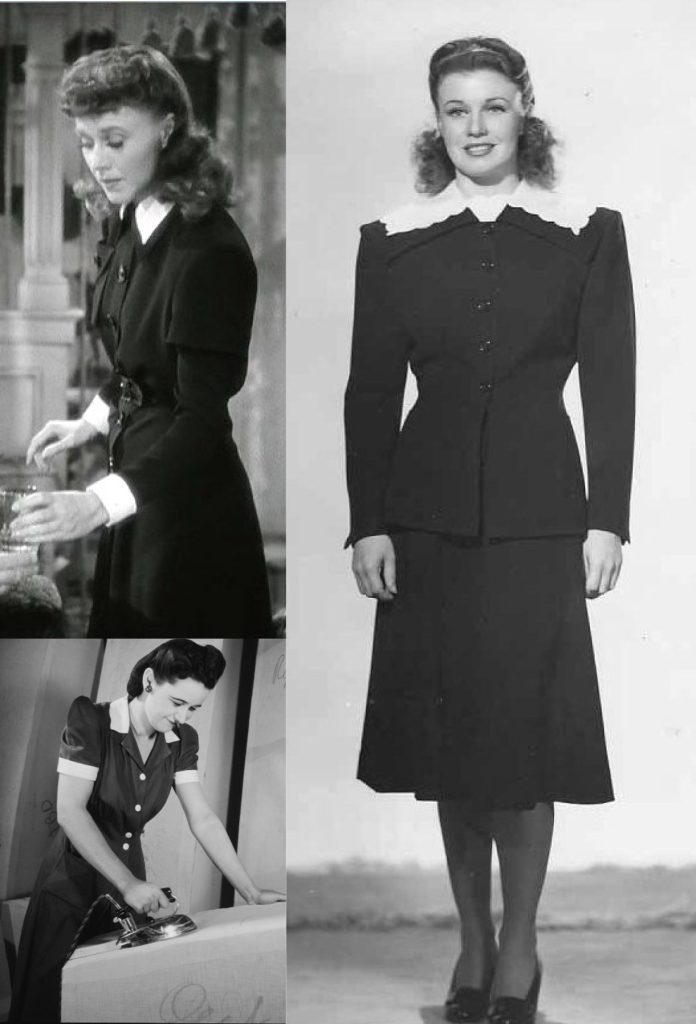

- One could easily make a ‘Kitty Foyle’ dress simply by adding a contrasting light collar and cuffs to a dark dress or suit like Rogers wore as ‘white collar’ girl Kitty Foyle in “Kitty Foyle” (1940).

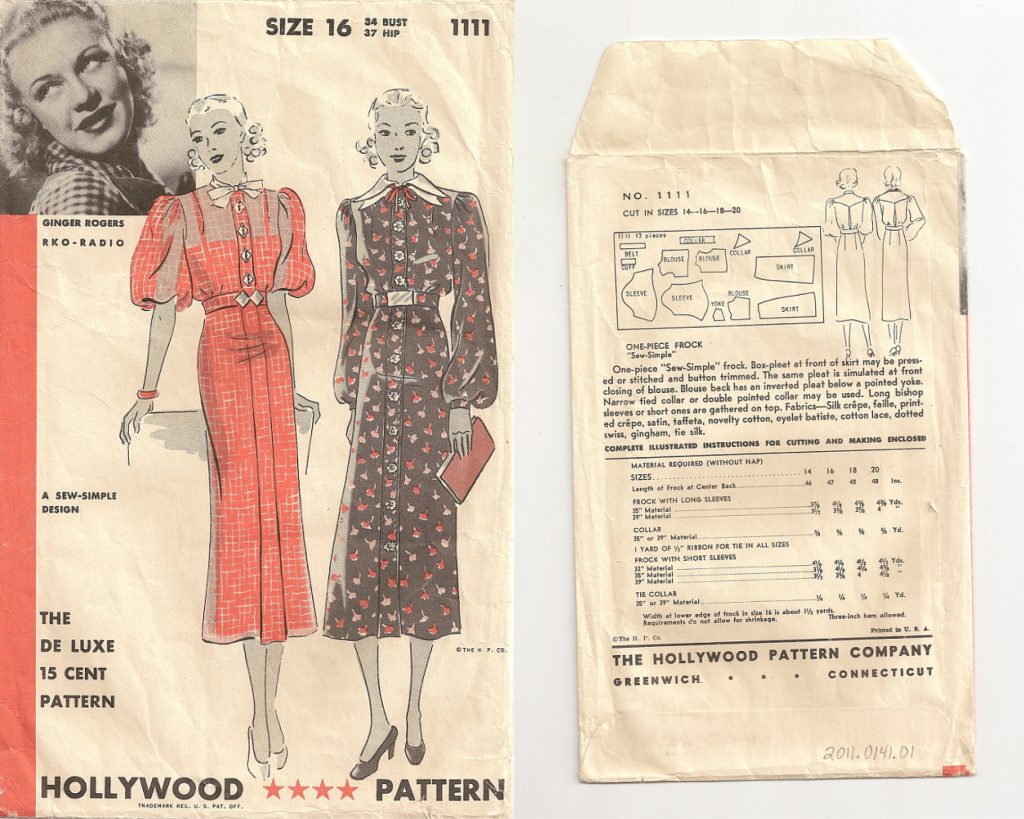

A variety of Rogers-inspired Hollywood dress patterns made Rogers’ stylish and glamorous film fashions available to the average American woman. During the 1930s and 40s, adaptations of film costumes were marketed and sold by companies such as The Modern Merchandising Bureau and Cinema Fashions; Referred to as “tie-ups” in which film studios received a percentage of the profits, many of these licensed fashions were offered in limited numbers to foster a feeling of exclusivity that was enhanced by the price of the garments which could range from $14 to $40. Copied styles were also manufactured by the thousands; these were available at all price points. For example, “Autographed Hollywood Fashions” were available in the Sears Catalog for $2.98.

IMAGES: Ca 1933 Ginger Rogers Dress Pattern, 2011.1041.01, National Museum of American History.

COSTUME HIGHLIGHT:

“Kitty Foyle,” 1940

In 1941, Ginger Rogers won an Academy Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role for her dramatic performance in “Kitty Foyle” (1940.) Her character’s dress, an ensemble of dark fabric and contrasting light collar and cuffs designed by Renié, became a popular style for women into World War II (1939-45). Called the ‘Kitty Foyle’ dress, it was modest, practical and easily copied or modified at home. The style has been explained as being intended for films, the large amount of white around the face reflecting light onto the face. Renié’s costume, shown on Rogers at left, made a strong statement with its dark colors and historic accents.

The same collar and cuffs could easily be added to a simple, button-down shirt style of dress like that shown here. The shirtwaist silhouette first rose to popularity during the 1930s with the development of the Junior dress industry. Part of its appeal lay in its versatility: the dress could be worn for a variety of purposes simply by using interchangeable buttons and cufflinks!

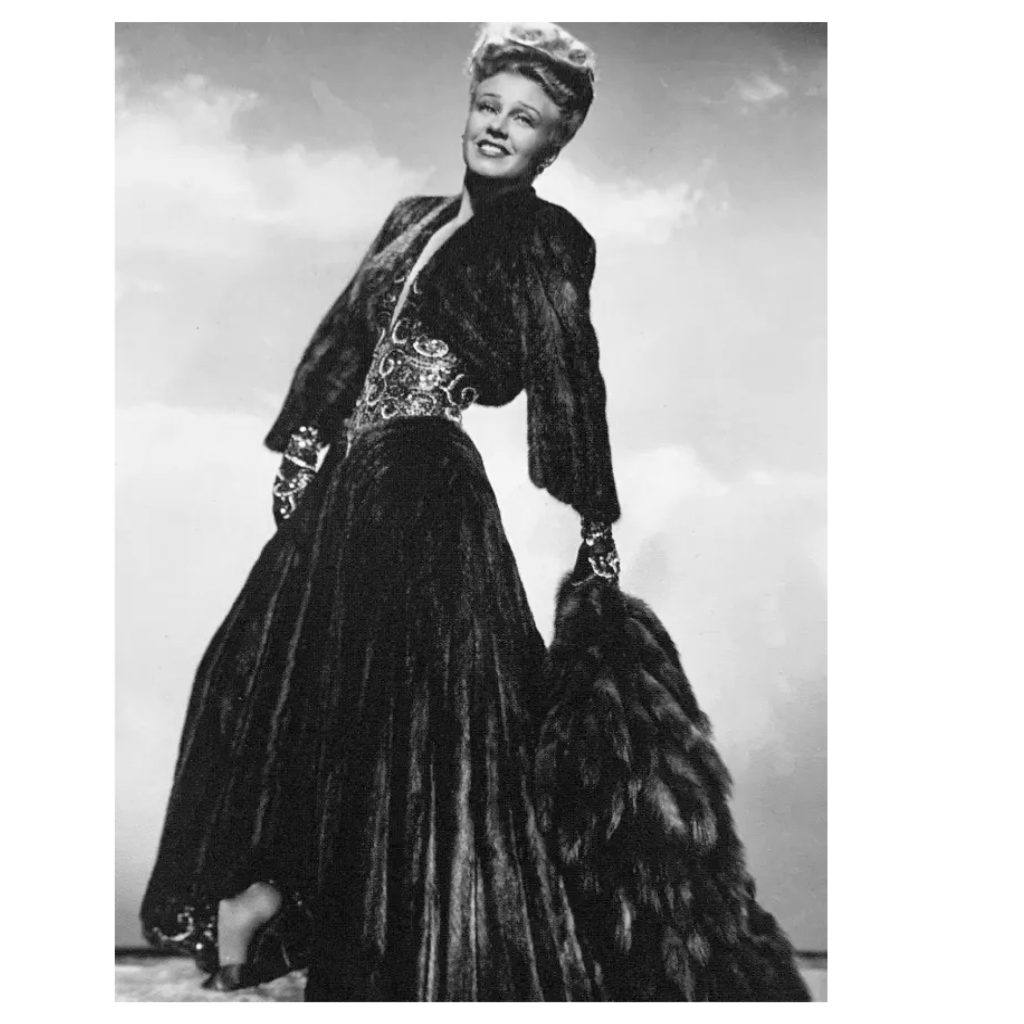

COSTUME HIGHLIGHT: “Lady in the Dark,” 1944

In 1944, Ginger Rogers determined a change in costume designer for the visually spectacular film Lady in the Dark. Rogers preferred the favored Hollywood designer Edith Head over Valentino, the original designer selected for the film. For the ‘Saga of Jenny’ sequence, Head and Director Mitchell Leisen designed a costume that was the most expensive garment ever designed at the time: a $35,000 mink, sequin and ruby encrusted dress. As only certain shades of mink photograph well, only specific skins were selected for the costume. In her book The Dress Doctor, Head described the selection process: “Director Mitch Leisen, Ginger and I studied the minks and picked out the most photogenic, Ginger sitting among them, stroking them like a child. Mink dress or gingham, my clothes never changed Ginger’s personality; she changed them.” Rogers wore two versions of the dress, one for singing and still close-ups and a lighter version for dancing. Rogers’ role in the film called for 25 costume changes.

“Mink dress or gingham, my clothes never changed Ginger’s personality; she changed them.” – Edith Head

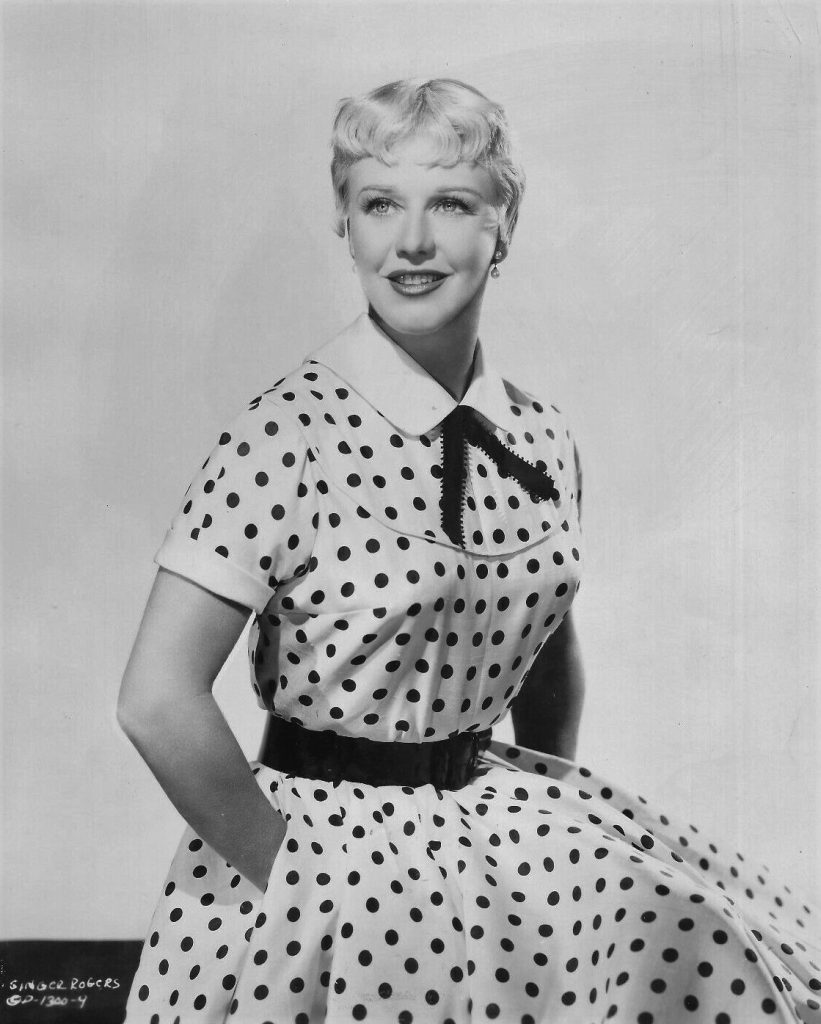

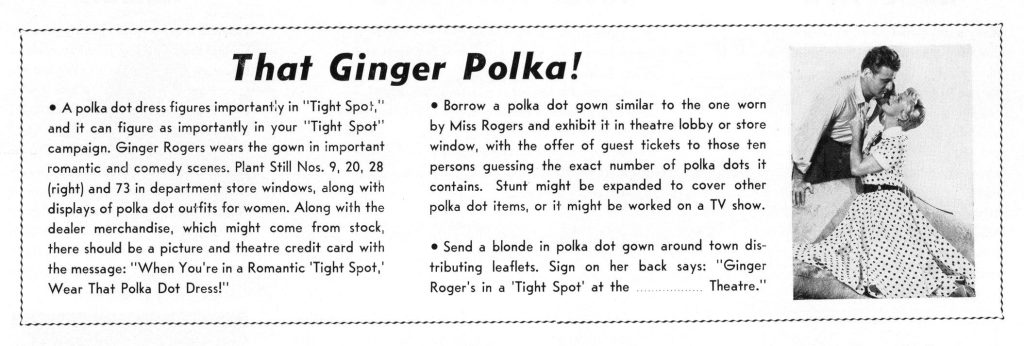

COSTUME HIGHLIGHT: “Tight Spot,” 1955

Pictured is a media still of Rogers from “Tight Spot” (1955) dressed in a polka dot dress by Columbia Pictures Head Designer Jean Louis that was shipped to New York from California for the film. As one of only two costume changes for the actress, the dress featured prominently in the film and in the Tight Spot media campaign. The dress also appeared for one day in the window display of a Fifth Avenue department store in New York during filming. “The scene called for Rogers, after four years of prison gray, to voice her delight upon seeing the polka-dotted gown.” According to the film’s pressbook, the department store temporarily displaying the gown was deluged with inquiries about the dress. “Hollywood is betting on a renewed interest in polka dot dresses as a result of ginger Rogers’ sensational appearance in Columbia Pictures’ ‘Tight Spot.'”

“Hello, Dolly!” 1965-67

From 1940 to 1980, Rogers appeared in a total of 18 theatrical performances, including as the lead in Broadway’s long-time smash hit “Hello, Dolly!” from 1965 to 1967. The national tour of the Broadway show stopped in over sixteen cities, with the final curtain call in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1968. At the age of 54, Rogers performed for 1,116 performances as Dolly Levi in “Hello, Dolly!” all while wearing a corseted satin bodice and skirt heavily weighted by thousands of hand-sewn beads, sequins and fringe.

“I sent my measurements to New York so that the turn-of-the-century dresses of velvet brocade and taffeta could be manufactured by the costume designer, Freddy Wittop. The minute I got there, I was to go in for my first fitting. [Opening night] I was wigged, rigged and ready to go on. I hadn’t been on the New York musical stage since Crazy Girl [1930]. But the moment the horse-drawn buggy halted in the middle of the stage, and I put down the newspaper that was covering my face, the audience went wild with applause (says she, modestly.) During my run on Broadway in Dolly, there had never been an empty seat in the house.”

IMAGE: Ginger Rogers as Dolly Levi in Hello, Dolly! (1965-67)

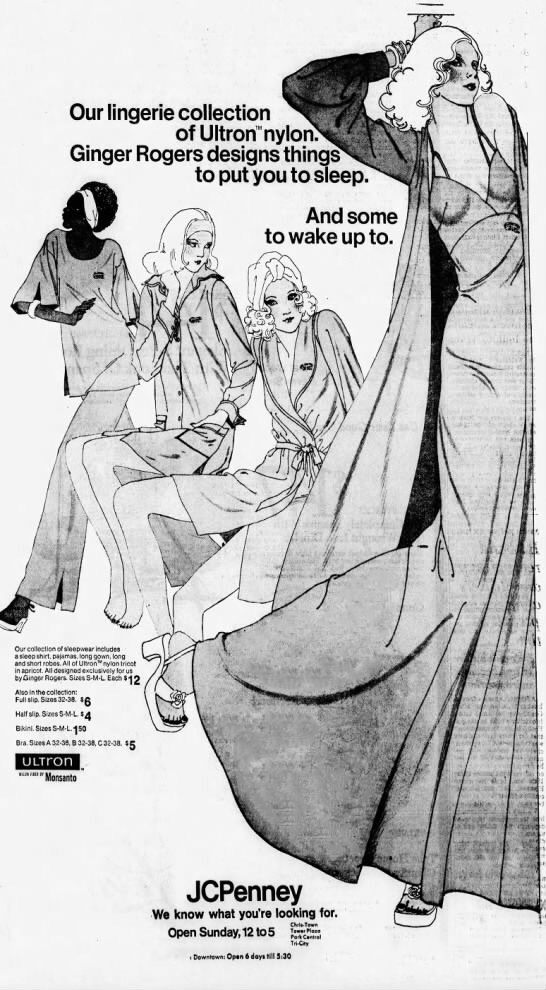

1972-75: JC Penney Fashion Consultant

From 1972 to 1975, Rogers acted as fashion consultant for J.C. Penney, designing clothes and lingerie under the label “Ginger Rogers for J.C. Penney.” Rogers hand-picked clothes for the mail-order catalog and traveled around the states to help women find affordable but fashionable clothing options. Of particular interest was lingerie. As she noted in her 1991 autobiography, J.C. Penney executives chose her as their representative due to her fashion knowledge and because they believed her famous legs would help the company sell pantyhose. “Her movie wardrobes in 70s films have come from the top theatrical designers and her private clothes from Parisians such as Grès, Saint Laurent and Givenchy. She will criss-cross the country with a 20-piece wardrobe, mostly red – “ I adore red, I hate flower prints.” Taylor, Angela. “Ginger Rogers – A Job in Fashion.” New York Times, April 25, 1972, pg 48.

IMAGE: Ginger Rogers for JC Penney Advertisement (1973)

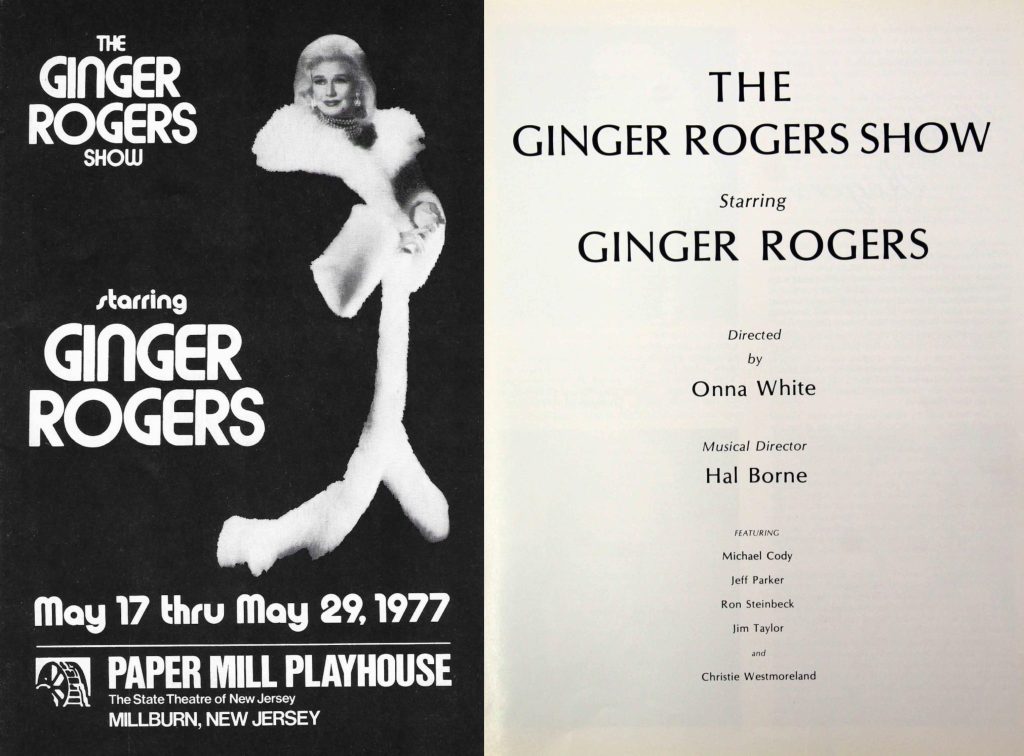

“THE GINGER ROGERS SHOW,” 1975-79

In the summer of 1975, Rogers made the decision that “instead of doing somebody else’s material, dialogue, and songs, [she] should do those musical numbers associated with [her] own career.” The Ginger Rogers Show was born that same year for which she asked notable Hollywood designer Jean Louis to design costumes. After the first show in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, the nightclub revue toured the U.S. and worldwide to Canada, Australia, Mexico, Argentina, and England through 1979. During these years of the show, Ginger Rogers effectively utilized viewers’ memories and associations with her own past performances and costumes to enhance the viewer experience, inherently drawing upon her appeal garnered as a young artist in the 1930s by incorporating recognizable elements from past work into her contemporary costumes.

As a seasoned performer by 1975, Ginger and legendary Hollywood designer Jean Louis (1907-1997) created costumes that not only visually connected past to present, but positively influenced how she was viewed by her audience. French-born Jean Louis first worked for fashion entrepreneur Hattie Carnegie, designing her iconic ‘Carnegie Suit,’ before becoming head designer for Columbia Pictures from 1944 to 1960 where he designed for other famous stars who wore his designs included Rita Hayworth, Marlene Dietrich, Vivien Leigh, Joan Crawford, Katharine Hepburn, and Marilyn Monroe whose sheer, sparkling gown designed by Louis in 1962 for President John F. Kennedy’s birthday celebration was worn by Kim Kardashian to the 2022 MET Gala.

As a seasoned performer by 1975, Ginger and legendary Hollywood designer Jean Louis (1907-1997) created costumes that not only visually connected past to present, but positively influenced how she was viewed by her audience. French-born Jean Louis first worked for fashion entrepreneur Hattie Carnegie, designing her iconic ‘Carnegie Suit,’ before becoming head designer for Columbia Pictures from 1944 to 1960 where he designed for other famous stars who wore his designs included Rita Hayworth, Marlene Dietrich, Vivien Leigh, Joan Crawford, Katharine Hepburn, and Marilyn Monroe whose sheer, sparkling gown designed by Louis in 1962 for President John F. Kennedy’s birthday celebration was worn by Kim Kardashian to the 2022 MET Gala.

IMAGE: “The Ginger Rogers Show” Playbill, Paper Mill Playhouse (May 29, 1955) Read the playbill. Gift of N. Johnston

COLOR AND COSTUME

Individuals, in this case Rogers’s viewers, judge others based on their clothes, and valuing uniqueness increases audiences’ ratings (or perceptions) of the status and competence of the wearer, an effect related to feelings of power. Rogers’ understanding of this complex relationship between dress, the body and the viewer experience is revealed in her costume on display, particularly through her ability to connect past and present and through her use of color. Color was another performance element Rogers understood in terms of viewer perception and experience. Like other variables that affect social perception, color can convey meaning which varies as a function of the context in which the color is perceived. Meanings of colors within a group are learned over time through repeated pairings with a particular experience or message. Color-in-context theory posits that the color can have functional as well as aesthetic value and that the mere perception of a color can evoke cognition and behavior through implicit affective cues.

The black-and-white spectrum of Ginger Rogers’ 1930s films was problematic as colors, fabrics and textures could appear dull on film. Pioneer Hollywood costumer Howard Greer recalled that “designing for the silver screen is a highly specialized talent. The dramatic flare [sic] necessary on film is often too flamboyant and exaggerated for private wear, and, by the same token, subtleties of color, fabric and drapery in three-dimensional clothes can be utterly devoid of personality and interest before the camera.” Therefore, most Hollywood designers attempted to use costume as an essential component of the narrative, to illustrate character traits or to further the film’s plot.

Costume ‘colors’ were selected to harmonize with the set design or to create a spectacle, to aid the narrative or illustrate character traits; fabric choices often also signified a character’s personality traits: wool tweed conveyed a serious nature; black satin a wicked one; tulle one of light-hearted innocence. When it came time to design an original gown for the 1935 film Top Hat, Ginger Rogers told designer Bernard Newman that she wanted something in the kind of blue found in a Monet painting. “It’s funny to be discussing color when you’re making a black-and-white film, Rogers confessed, “but the tone had to be harmonious.” The resulting gown was exactly as Rogers had envisioned, complete with $1,500 worth of ostrich feathers. The color blue was favored by Rogers throughout her career, as evident by this beautiful blue chiffon gown with blue-dyed fox fur trim designed by Jean Louis for The Ginger Rogers Show in 1975.

Full color became more common in motion pictures during the 1940s and 1950s, further impacting the viewer experience as it created mood, directed attention and evoked emotions from the audience. Ginger Rogers understood this performative element as applied to costume and how it impacted viewer perception.

Two colors in particular have strong psychological associations in American culture: black is frequently associated with power, aggression and death; red with energy, warmth, and sexuality. As a function of these associations between colors and experiences, messages, or biological tendencies, color acts as a stimulus; people either inherently approach or avoid. Rogers, who drew fans for over six decades, clearly understood these associations of color and chose her costume colors to attract viewers. Pink, a shade of red – and Ginger’s favorite color – appears frequently in her costumes within the exhibit, as does the color black. The color

Pink underwent a ‘shocking’ transformation in the 1930s to which Rogers visually links with her own 1970s bright pink feather dress below!

Bright pink was introduced as a fashion color by Elsa Schiaparelli, pioneering Surrealist designer, in 1937, as ‘shocking pink,’ a vibrant shade compared to many of the demure pale pinks that dominated the period. ”The violent hue was startling, overt – femininity as warfare. It represented a woman who was liberated and sexually brazen, the kind of woman Schiaparelli wanted to dress” (Byland, Veronique. Dress Code (2023) 82-83). Legendary fashion editor Bettina Ballard wrote, “she [Schiaparelli} changed the outline of fashion from soft to hard, from vague to definite.” In her 1954 autobiography, Schiaparelli herself called the color “life giving like all the light and the birds and the fish in the world put together, a color of China and Peru but not of the West.” The color quickly caught on beyond its creator and became a sort of bombshell plumage, the color of Marilyn Monroe’s dress in Gentleman Prefer Blondes, as she stood silhouetted against a group of men dressed in black tuxedos. Rogers utilized this color in her later career to help audiences visually connect her own pioneering career of the 1930s to her present-day revue.