ARTS AND CRAFTS DESIGN (RE)FORMS: Decorative Forms

The major innovation of the Arts and Crafts movement was its ideology rather than promotion of a specific style. Its major tenets – raising the status of the craftsman and promoting respect for native materials and traditions – were reflected primarily in architectural and decorative art forms including print, home furnishings, wall paper, wood carving, metalwork, stained glass, ceramics, jewelry, textiles, and more. The Arts and Crafts community was open to the efforts of both the professional and non-professional, encouraging the participation of amateur artists and students, as well as women who, for the first time, could begin to take an active role in developing new forms of design.

ARCHITECTURE AND WOODWORK Many Arts and Crafts leaders had trained as architects, resulting in a common culture of ‘total design,’ the goal of which was a harmonious blend of both structural and decorative elements of the home. Architectural ideals included the beliefs that “design should be dictated by function, that vernacular styles of architecture and local materials should be respected, and that new buildings should integrate with the surrounding landscape.”3 Unlike the English Arts and Crafts ideals that avoided mass production, many American architects welcome it – using metal screws to hold beams in place and creating machine-produced kit homes. Many internationally recognized architects in the movement, including Philip Webb (1831-1915), Charles Voysey (1857-1941), Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott (1865-1945), and Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928), produced and sold designs in a variety of other decorative forms such as textiles, ceramics, home furnishings, and metalwork.

The terracotta angel sculpture below is an example of the Arts and Crafts movement’s decorative architecture. Made by the Winkle Terra Cotta Company of St. Louis, Missouri for the exterior of the former Title Guaranty Building in St. Louis, the sculpture represents not only a Renaissance Revival during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but also the revitalization of the female form in art of the period. As stated by Arthur Mehrhoff in Fallen Angel: A Case Study in Architectural Ornament (2016), “Ever since the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893 proclaimed an American Renaissance to the world… angels and/or winged figures like those on the Title Guaranty Building proliferated across the rapidly developing urban landscape”36.

Women also found opportunities for work in the field of Arts and Crafts architectural design. Architect Irving Gill (1870-1936) taught Hazel Waterman (1865-1948) to do architectural drawing at his studio in San Diego after the death of Waterman’s husband in 1903. After training, Waterman wanted to become an architect in her own right. Commissioned to design three houses, Gill supervised and supported her work. Opening her own office in 1906, Waterman designed projects as a professional architect while raising her three children.18 Julia Morgan was also one of the best known architects of the period. Initially denied entrance to the all male Ecolé des Beaux-Arts in Paris, she was eventually granted admission and became the first woman graduate. She opened her own architectural firm in her native California in 1904, creating a California style with Arts and Crafts characteristics.

Woodwork was intrinsic to Arts and Crafts interiors. Decorative trim and furnishings often conveyed Medieval ideals of the movement, such as Elbert Hubbard’s Little Journeys table pictured below. Hubbard used mortice and tenon joints, a centuries old method in which a tenon (tongue) is inserted into the mortice hole at a right angle and locked into place (see detail image of joint structure.) Other American entrepreneurs also embraced the Arts and Crafts movement and sought to profit from it. By 1910 hundreds of furniture companies throughout the United States were manufacturing Arts and Crafts furniture of varying quality. Fred Albert Dennett (1849-1920) established the Wisconsin Chair Company in 1888 and experienced rapid growth. Within ten years, the company employed more than 600 workers and by 1910 was producing 475,000 chairs per year, making it one of the largest furniture manufacturers in the United States.11 That same year Dennett launched Lakeside Craft Shops in Ohio, specializing in small pieces of furniture such as footstools and magazine stands. The name “Lakeside Craft Shops” alluded to a collective of craftsmen producing artistic, hand-made products for the home. Even the company motto, “Art in the Home,” captured a major tenet of the Arts and Crafts Movement.11

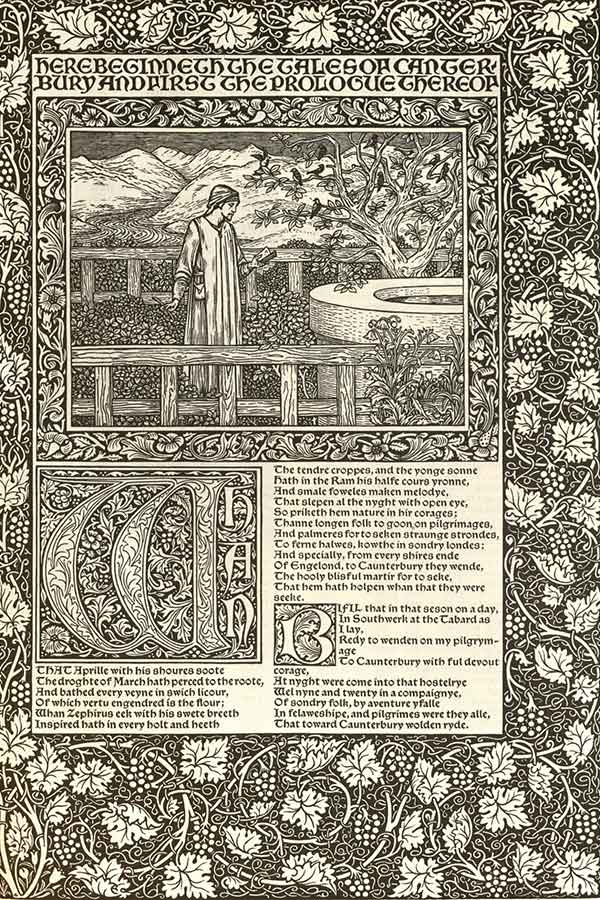

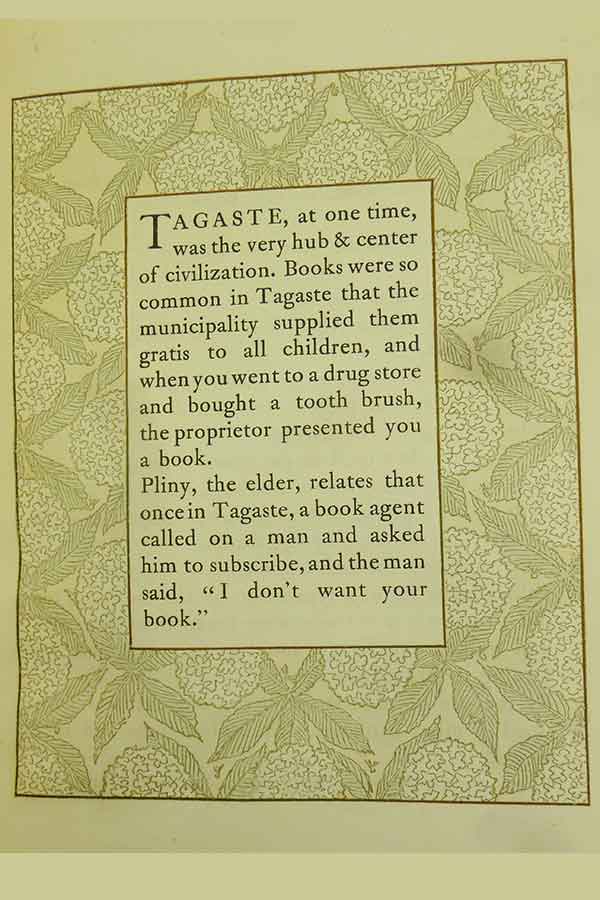

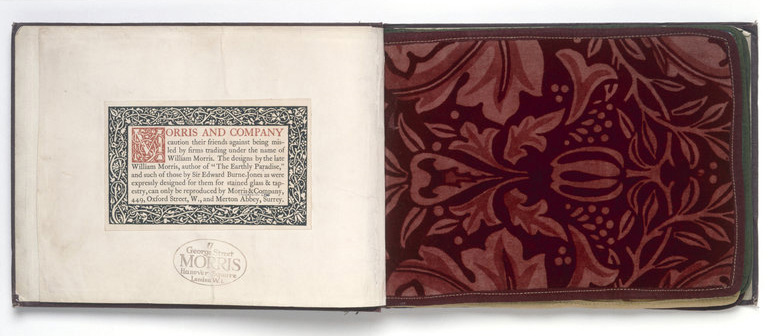

PRINTING Poet, artist and political theorist William Morris mastered the art of woodblock printing to create some of the most recognizable wallpaper and textile patterns of the 19th century. His wallpaper designs were printed by hand using carved, pear woodblocks and natural, mineral-based dyes. Morris’s own Kelmscott Press printed works such as “The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer” (1850) and “Ballads and Narrative Poems” (1893) by Dante Gabriel Rosetti. In America Ebert Hubbard of the Roycroft Press (aka The Roycroft Shops) printed a variety of elaborate texts and magazines with the assistance of both his first and second wives Bertha Crawford Hubbard and Alice Moore Hubbard. See examples of these works from the University of Missouri’s Special Collections and Rare Books.

![Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. Ballads and Narrative Poems. [Hammersmith]: Printed by William Morris at Kelmscott Press (1893); MU Ellis Special Collections Rare Folio, University of Missouri, Columbia](https://mhctc.missouri.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/7-9.jpg)

![The History of Reynard the Foxe [done into English out of Dutch] by William Caston [corr. By Henry Halliday Sparling] Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press (1893) MU Ellis Special Collections Rare Folio, University of Missouri, Columbia">](https://mhctc.missouri.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/8-10.jpg)

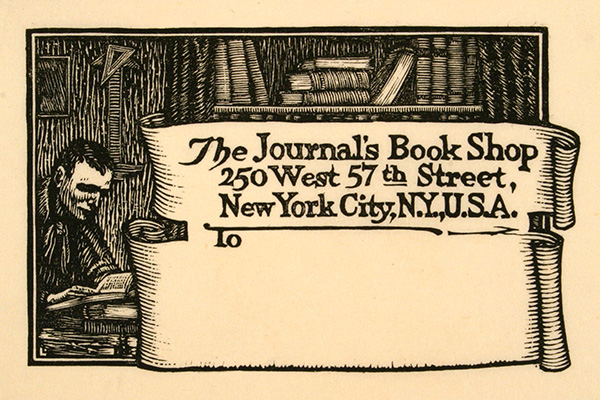

American illustrator Julius John Lankes (1884-1960) also helped elevate woodblock prints beyond illustrations in commercial product to recognition as a fine art. Heavily influenced by William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement, Lankes produced almost 1,300 works in the woodblock medium. The J.J. Lankes Collection at the University of Missouri’s Museum of Art and Archaeology includes twenty-two woodcut prints on paper, such as those below, as well as an additional eight woodcut prints after designs by Lankes.

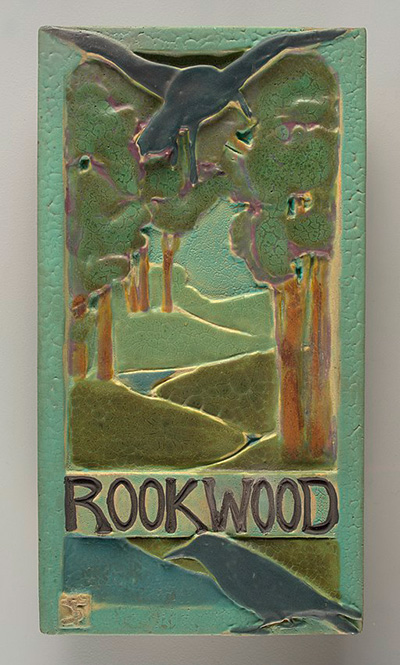

CERAMICS As American artists sought to imitate the English Arts and Crafts style, women were fundamental in forming an early grassroots movement of clubs, schools and other organizations. The first women’s ceramic club in America was the Cincinnati Pottery Club founded by Mary Louise McLaughlin (1847-1939) in 1877 and run entirely by women officers.18 Grassroots movements evolved into an organized network of individuals and groups and by the mid-1880s these early efforts had “caused a massive expansion in Arts and Crafts production” with women employed in various design, production and support positions.18 One example is that of Rookwood Pottery. Forbidden to learn painting on canvas, artist Maria Longworth-Nichols (1849-1932) turned to ceramics instead, and founded Rookwood Pottery in 1880. She quickly built the company into an internationally recognized ceramics studio. At Rookwood women represented almost 60% of the decoration department and occupied several key positions.18

A hierarchy often existed within Arts and Crafts ceramic production which involved a top designer who designed the ceramic forms, makers who crafted the works in clay, and decorators who painted and glazed the finished clay forms. This method of production encouraged the participation of amateur artists and students, as well as women who, for the first time, could begin to take an active role in developing new forms of design. One such opportunity was provided by Newcomb College Pottery which operated in New Orleans from 1894 to 1941. The pottery was created and operated by young educated women enrolled in Newcomb College. Over 90 students created approximately 71,000 total pieces of pottery while the school was in operation.8 Another example was that of Overbeck Sisters Pottery begun in 1911 as a way for the Overbeck sisters to support themselves. The four sisters – Margaret (1863-1911), Hannah (1870-1931 ), Elizabeth (1875-1936), and Mary (1878-1955) – are known today as true adherents to the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement, having formed every piece by hand with no molds. Their designs appeared regularly in monthly magazines and won many design competitions.

However, these women were often overshadowed by the male Arts and Crafts practitioners who followed later. The Grueby Faience Company was founded in 1894 by well-known metal wares designer William Henry Grueby (1867-1925). Grueby teamed with George Prentiss Kendrick (1850-1919) to create arts and crafts tiles and other pottery forms in vegetative designs with soft matte glazes, including the iconic cucumber-green matte glaze for which the company would become known.7

JEWELRY, METAL WORK AND LEATHERWORK Arts and Crafts jewelry designers chose to feature the inherent qualities of stones and other metals, another example of the movement’s “truth to materials” that strongly emphasized the beauty of good design. Aesthetics included fewer precious gemstones, preference for silver over gold, and use of painted enamel to demonstrate a piece’s handcrafted qualities. Jewelry was another area of Arts and Crafts design in which women such as Florence Koehler (1861-1944) and Marie Zimmermann (1879-1972) received real recognition.

As much as woodwork and ceramics, decorative objects crafted of copper, brass, silver, and iron were intrinsic to the Arts and Crafts home. Hand wrought metal work ornamented building exteriors as well as interiors in the forms of rails, door furnishings, lanterns, book ends, chargers, and more! Clothing, jewelry, shoes, and handbags were also accented with metal. Accomplished metal artist Otto Heintz (1877-1918) was born into a family of manufacturing jewelers through whom he learned skills of jewelry and metalwork. His company, the Arts Crafts Shop in Buffalo, New York, designed and manufactured copper items with colored enamel decorations. In 1906 the name was changed to Heintz Art Metal Shop after which the artist shifted to bronze as the base material for his designs and sterling silver as ornamentation. Heintz patinas, like those of other Arts and Craft metalwork, were factory applied finishes, produced with chemicals and heat. In 1912 Heintz patented a process of applying sterling silver overlays to bronze without the use of solder.9

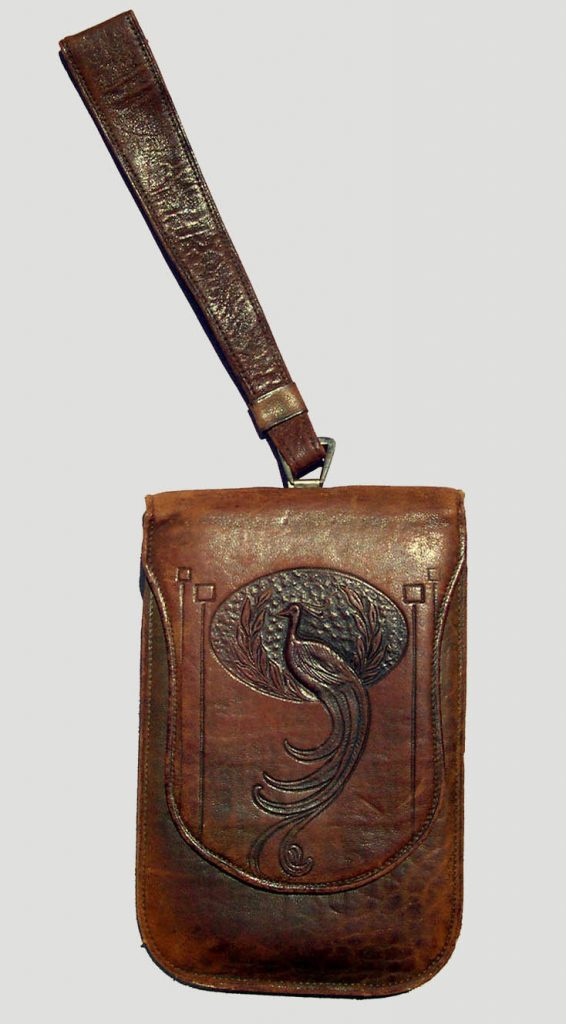

The American Arts and Crafts movement also left a rich assemblage of forms created from hand-tooled and decorated leather. Handbags, toiletry cases, wallets, books, wastebaskets, chair pillows, and other household items featured tooled, painted or burned designs similar to those used in embroidery: native flowers, birds like hummingbirds and peacocks, and geometric and contemporary-looking shapes. Regional design motifs became apparent, with Roycroft and Cordova Shops leading the way in the Northeast while in the Midwest, practitioners were frequently influenced by the Prairie Style.44

TEXTILES Textiles and embroidery were key elements of Arts and Crafts interiors. Hard furniture needed cushions for comfort; curtains were needed to exclude drafts; carpets added warmth to wood and tile floors; table squares and runners brightened interiors that could often be austere.20 Designs produced within the movement ranged from home craft to industrial mass production. Patterns translated three-dimensional nature into two-dimensional stylized representations of nature rather than imitations. The guiding principle of truth to materials was applied to tapestries, carpets, woven fabrics, clothing accessories, and embroidery. Motifs by U.S. designers also featured geometric forms, black outlines and rich golds, greens, reds, and browns, colors which harmonized with those used in the Craftsman style of decorating.

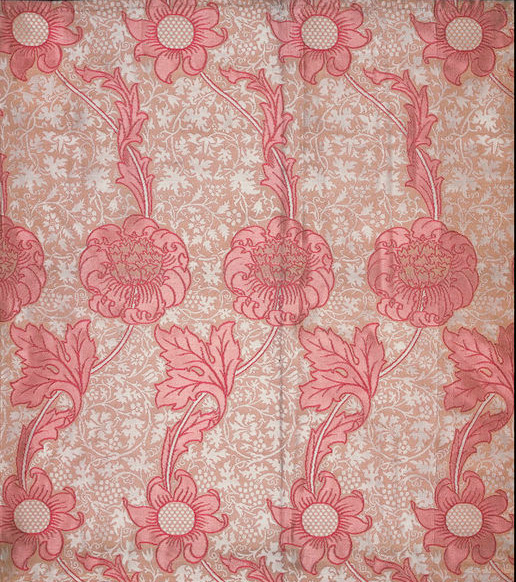

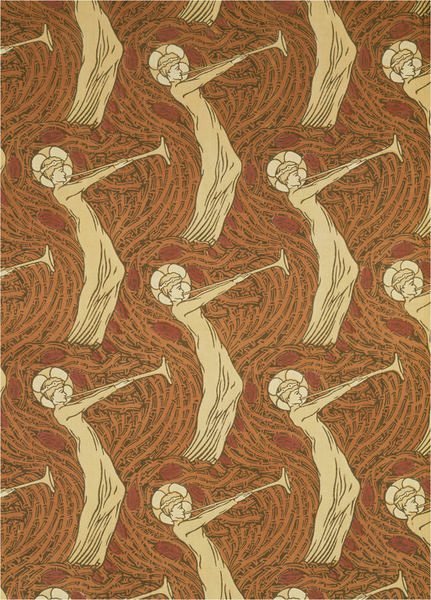

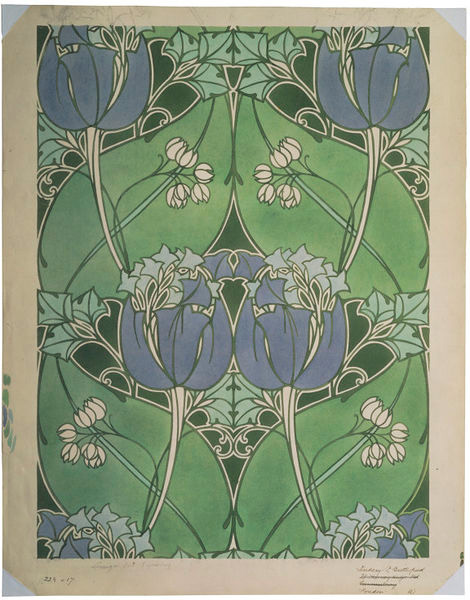

Printed textiles use hand-carved woodblocks or rollers in patterns inspired by both nature and history. Early textiles from the 1860s emulated medieval tapestries and large mirror motifs often reflected blooms found in an English garden such as tulips, marigolds, honeysuckles, and sunflowers. Organic dyes such as cochineal, indigo and weld were expensive but resulted in more natural effects with subtle variations.

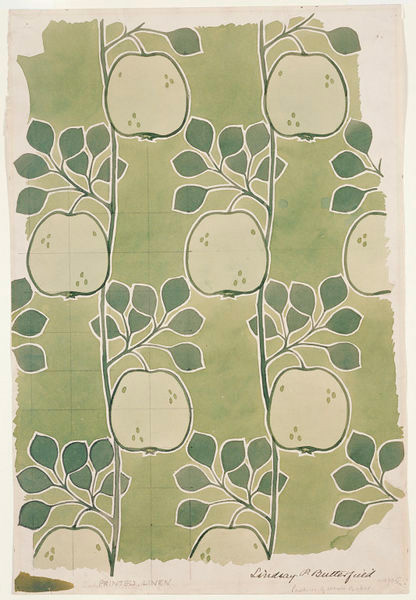

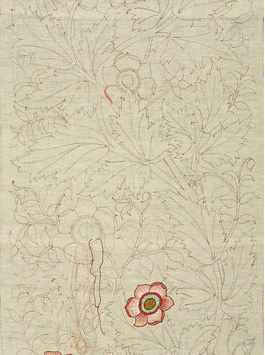

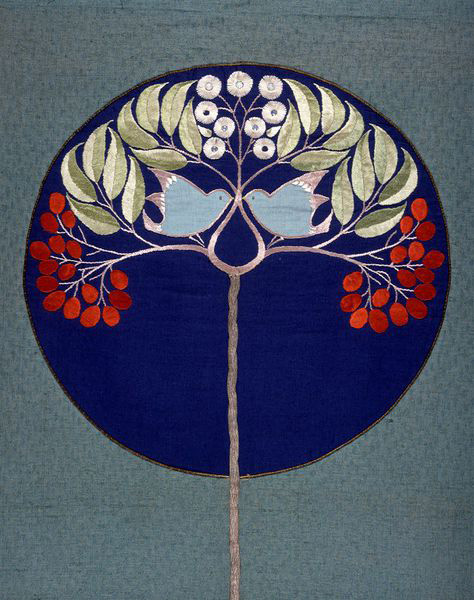

Textile manufactures employed freelance designers who provided patterns for a variety of home fabrics such as curtains, pictures, cushions, bed covers, floor coverings, wall hangings, and screen panels. One of the most successful freelance designers of patterns in the Arts and Crafts style was Lindsay Butterfield (1869-1948) whose wallpaper and textile patterns were created using both block-printing and roller-printing. Charles Voysey (1857-1941) was an architect and prolific decorative designer who sold variations of similar patterns dominated by birds, deer, hearts, flowers and trees to a number of different manufacturers. William Morris & Co. hired architect Philip Speakman Webb (1831-1915) and John Henry Dearle (1860-1932) to produce take-home embroidery kits and other decorative designs. The ‘started’ panel below by Dearle includes “cotton ground, painted design, and colored silks with areas completed so that the recommended technique could be followed at home”33. Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott (1865-1945), one of the most highly regarded architects at the turn of the twentieth century, also designed furniture and textiles using embroidery to decorate textiles used in his interiors. His wife, Florence Kate Nash (1862-1939), embroidered the cotton and hemp screen panels of stylized birds and trees shown below using silk thread, plaited silver braid and gold cord.32

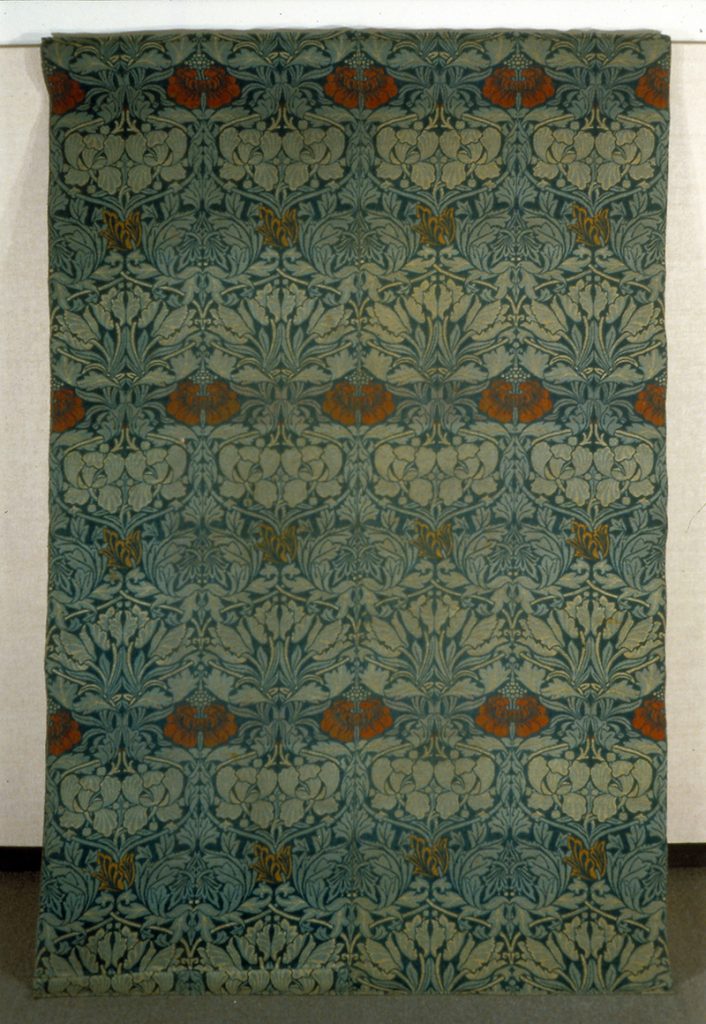

In Britain textile designer William Morris (1834-1896) designed and sold household furnishings that were sought after for their elegant and colorful patterns and high-quality materials. A self-taught embroiderer, wood engraver, and weaver, Morris and his friends Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Philip Webb, Peter Marshall (1830-1900), and Charles Faulkner (1833-1892) founded Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company in 1861 which would become one of the most influential design firms of the Arts and Crafts movement.10 Textiles were very profitable and included embroidery, prints, woven fabrics, tapestries, and carpets.

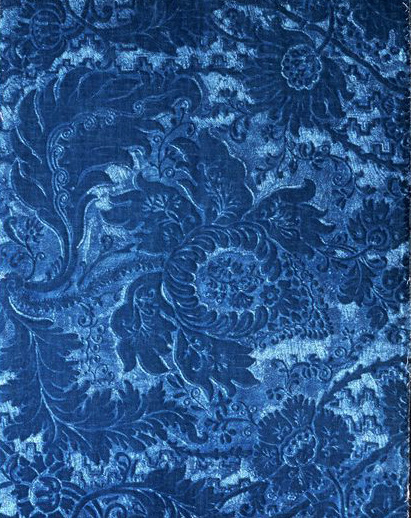

In the 1870s printed velveteens became very fashionable and Morris & Co. exhibited samples at the first Arts and Crafts Exhibition in 1888. See the 1876 sample book below with designs by Morris and John Dearle (1859-1932). The underlying principle of Morris’s patterns was revolutionary in its movement but with a sense of order, setting his textiles apart from the period’s dominant rigid, formal patterns.10

Morris had a progressive attitude towards women as co-workers and promoted the work of female designers in his shop. His daughter, Mary (May), assisted in the shop at an early age and took over the successful embroidery branch of the company in 1885 at age 23. In 1907 Mary co-founded the Women’s Guild of Arts because the existing Art Workers Guild did not admit women. She adopted many of her father’s design principles into her work, embracing both flora and fauna.

Artist and architect William Baumgarten (? – 1908) brought traditional European weaving techniques to the U.S. After meeting the Foussadier family, former weavers of the Royal Windsor Tapestry Manufactory, in Aubusson, France, Baumgarten brought them to New York and established the first Gobelin tapestry looms in the United States in 1893 under the name William Baumgarten & Company. The tapestry workshop was extremely successful with twenty-two antique European looms and over seventy employees, most of them from France, at its height.21 The model of the Baumgarten tapestry workshop was similar to a medieval village, with weavers managed in a skilled hierarchy from apprentice to master. All functions – designing, dyeing, weaving, and repairing – were housed within one compound.21 This system effected the types of tapestries produced and Baumgarten tapestries generally reflected well-known European styles that fit well within the popular revival décor of the period. Baumgarten designed the Fifth Street mansion for William Henry Vanderbilt in New York, tapestries and decorative paintings for William Welsh Harrison’s Grey Towers Castle in Philadelphia, and was original designer of several period rooms at New York’s Plaza Hotel in 1907.

Former Baumgarten & Company designer Albert Herter (1871-1950), well-known as a painter and illustrator, founded his own tapestry studio Herter Looms in 1909 after the closing of Herter Brothers, a design company co-founded by his father Christian Herter (1839-1883), in 1906. Influenced by the work of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement, Herter created tapestries and mural paintings in a medieval style for statehouses, public libraries and a variety of other public buildings. Tapestries and rugs often referenced historical time periods and subject matter including mythological and historical figures of ancient Greece and Rome and aesthetics of Medieval and Renaissance periods, as well as Asian and Persian influences.

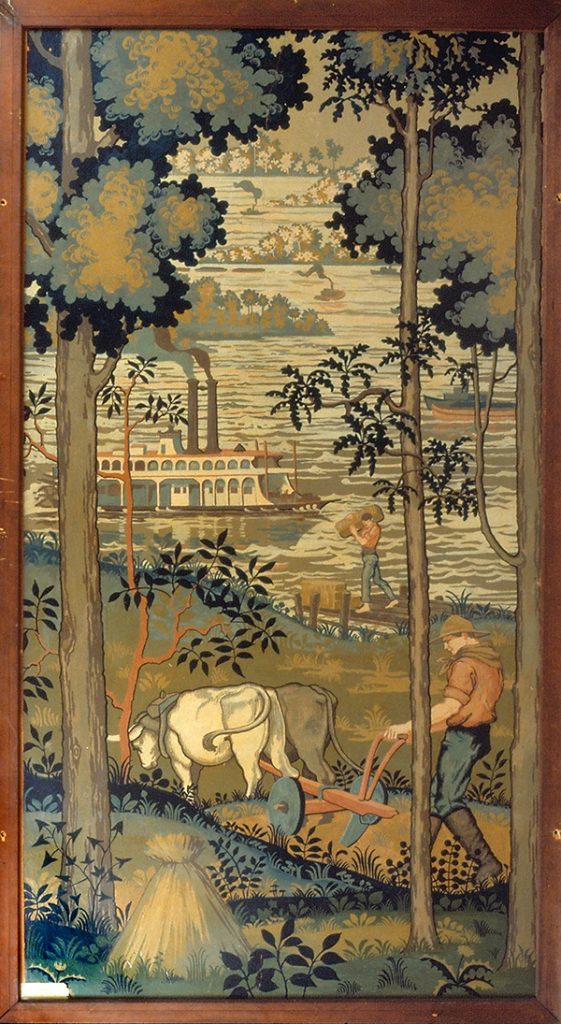

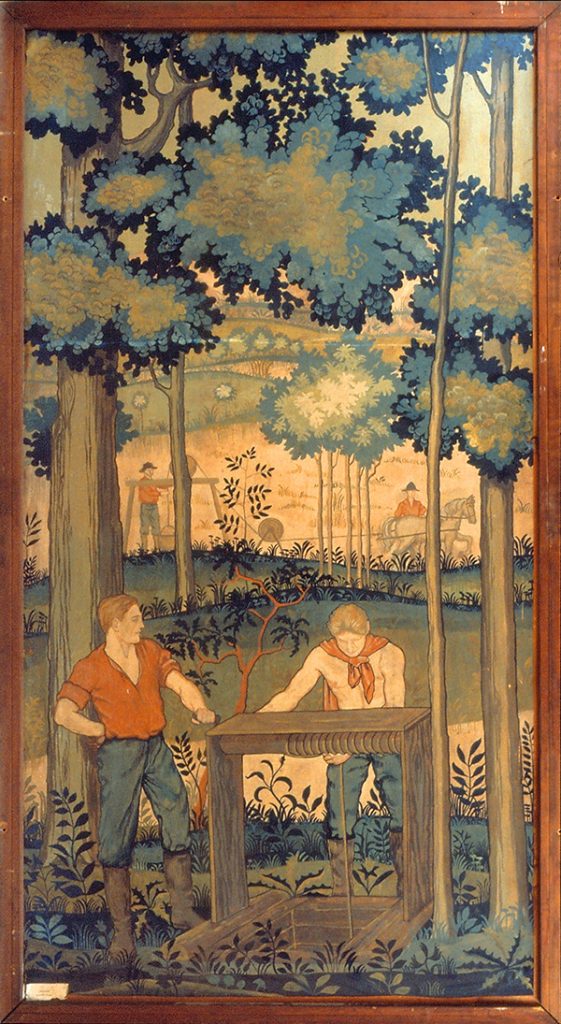

Another former Baumgarten employ, Norwegian-American artist Lorentz Kleiser (1879-1963), was commissioned to create tapestries for the newly-built Missouri capitol building in Jefferson City, Missouri in 1923. Kleiser utilized tapestry studies (below) from full-size drawings to create eleven tapestries for the building’s Senate Lounge. Many of Kleiser’s tapestry designs, including the Missouri capitol tapestries, were dyed using vegetable materials and woven by hand.48 49 During his distinguished career, Kleiser had worked briefly for Herter Brothers, a prominent New York design firm, and for William Baumgarten & Company, founded by William Baumgarten. After Baumgarten’s death in 1908, Kleiser opened his own New York studio in 1909 that became Edgewater Tapestry Looms in 1913.5 Kleiser quickly gained international recognition for weaving large custom tapestries of high quality for private clients such as John D. Rockefeller and Luther Stark, as well as textiles for museums, hotels, and state capitol buildings.

3 http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/history-of-art/arts-and-crafts.htm Retrieved April 10, 2019

5 Laffer, Christine. “Low Tech Transmission: European Tapestry to High Tech America.” Textile Society of American Symposium Proceedings, Textile Society of America (2010); University of Nebraska-Lincoln Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1030&context=tsaconf

7 http://gruebypottery.com Retrieved March 2019.

8 http://newcombpottery.com. Retrieved March 2019.

9 www.heintzcollector.com Retrieved April 2019.

10 William Morris: Designing an Earthly Paradise Exhibition Catalog, Cleveland Art Museum. 2017.

11 “Fred Dennett and The Lakeside Craft Shops.” Journal of Antiques & Collectibles. February 29, 2016. http://journalofantiques.com/features/fred-dennett-and-the-lakeside-craft-shops/. Retrieved June 2019.

18 Zipf, Catherine W. The American Arts and Crafts Movement and its Women Practitioners. http://journalofantiques.com/features/wrought-by-her-hands/

20 Euler, Laura. Arts and Crafts Embroidery. Atlegn, Pennsylvani: Schifer Publishing Limited. 2013.

21 William Baumgarten & Company; https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/951501 Retrieved May 2019.

31 http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O88924/the-angel-with-the-trumpet-furnishing-fabric-horne-herbert-percy/. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Retrieved May 2019.

32 http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O108831/screen-panel-baillie-scott-mackay/. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Retrieved May 2019.

33 http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1364285/anemone-screen-panel-dearle-john-henry/. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Retrieved May 2019.

36 Mehrhoff, Arthur. “Fallen Angel.” Muse Vol 50 (2016):75-89.

44 Lees, Daniel. “Artistic Leather of the Arts and Crafts Era.” Schiffer Publishing Ltd. 2009.

48 Hall, Douglas E. “Images of America: Edgewater.” (2005) Arcadia Publishing: Charleston SC, Chicago IL, Portsmouth, NH, San Francisco, CA.

49 Complete Report of the Capitol Decoration Commission 1917-1928. Pickard, John, president. (1928)

50 Libby Horner and Gillian Naylor eds. Frank Brangwyn 1867–1956. (2007) Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds Museum and Galleries [Leeds]; Groeninge Museum [Bruge]