Missouri Women: Suffrage to Statecraft (2020)

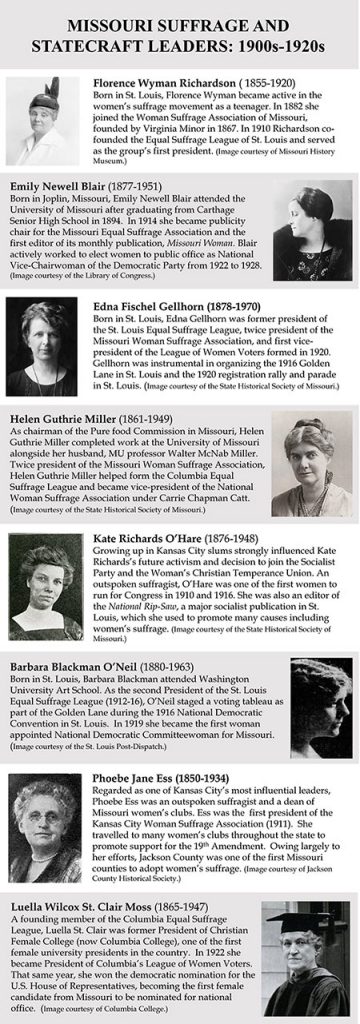

As early as the 1840s, Missouri women actively fought for equal voting rights. After ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, trailblazing women in Missouri politics continued the fight for equal representation.

The fight for women’s right to vote in the United States began in the mid-nineteenth century. The 1848 Seneca Falls Convention for equal rights, organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, was the starting point from which a national woman suffrage movement emerged. During the 1900s and 1910s organized promotional efforts throughout Missouri and the nation included picket lines, parades, marches, lectures, letters, educational classes, petitions, and more. These efforts were ultimately a success. Missouri became the 11th state to ratify the federal suffrage amendment on July 3, 1919. Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify in August 1920, and U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby certified the ratification on August 26, 1920, creating the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This action permanently changed the face of the electorate, giving women not only the right to vote, but also more opportunities to participate in public office.“MISSOURI WOMEN: SUFFRAGE TO STATECRAFT” surveys the decades-long struggle for women’s suffrage by highlighting the roles of Missouri women in the national suffrage movement and the trailblazing women in Missouri politics who opened the doors for others to participate in the democratic process.

Exhibited at the State Historical Society of Missouri’s Center for Missouri Studies, in Columbia, Missouri from March 14 to July 25, 2020. “Missouri Women: Suffrage to Statecraft” was curated by Nicole Johnston and Jean Parsons of the Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection at the University of Missouri, and Joan Stack, Curator of Art Collections, of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

Exhibition Views

Early Suffrage: 19th Century

“We believe that all persons who are subject to the law, and taxed to support the government have a voice in the selection of those who are to govern and legislate for them… We therefore pray that an amendment may be proposed striking out the word ‘male’ and extending to women the right of suffrage.”

— Excerpt from MINOR petition presented to the Missouri State Legislature (1867)

A national woman suffrage movement began at the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention held in Seneca Falls, New York. Participants included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Mary M’Clintock, Martha Coffin Wright, and Jane Hunt. Susan B. Anthony did not attend the convention, but met Stanton in 1851, and spent the rest of her life fighting for women’s equality. The suffrage debate began in the Midwest when many of the Eastern suffragists toured various states. Lucy Stone, publisher of the Woman’s Journal, spoke in St. Louis before a record crowd in 1853. The suffragists were quite successful in the west (see map). In 1869 Wyoming granted universal suffrage to women over the age of 21; the Utah Territory followed in 1870. The state of Utah granted full suffrage in 1896.

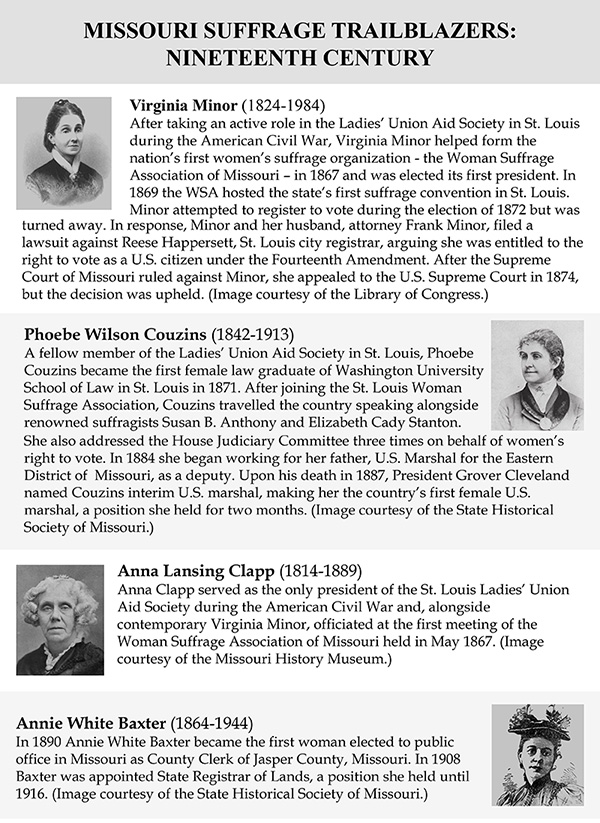

In Missouri, the suffrage movement rose from women’s aid organizations such as the St. Louis Ladies Union Aid Society. In 1867 a group of women, many of whom had shared efforts in the Aid Society, met in St. Louis to discuss women’s suffrage. From this meeting, the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri was formed, the first of its kind in the U.S. whose sole objective was the enfranchisement of women. Members included president Virginia Minor, Phoebe Couzins, Lucretia Hall, and Anna Clapp.

In 1868 the Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship and its rights to all persons born or naturalized in the U.S. This same amendment, argued Missourians Virginia and Frank Minor, also protected women’s right to vote as women were citizens and entitled to all the benefits of citizenship. A nationwide pattern of disobedience emerged, a “new departure” in which women all over the country demanded to vote at their local polling places. Minor herself attempted to register at the St. Louis County Courthouse in 1872 but was turned away.

Minor and her husband filed a lawsuit against St. Louis City Registrar Reese Happersett, but lost in the lower circuit court and again in the Missouri Supreme Court in 1873. In a nationally significant decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Minors in 1874, stating that “the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone,” and upheld the right of individual states to decide which citizens could vote. Between 1867 and 1901, suffragists in Missouri petitioned 18 times for a state constitutional amendment enfranchising women. Only eight came to a vote in the Missouri legislature. Missouri lawmakers voted against woman suffrage each time.

Many suffrage groups focused on piety, morality and domesticity. This became a problem when suffrage organizations began to align with the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1874. Its earliest presidents were Missouri women who created strong affiliations to the organization through-out the Show-Me state. By the next century, this shared platform became a hindrance to women’s enfranchisement as alcohol lobbyists actively fought it. By early 1910, suffrage groups began to distance themselves from the WCTU.

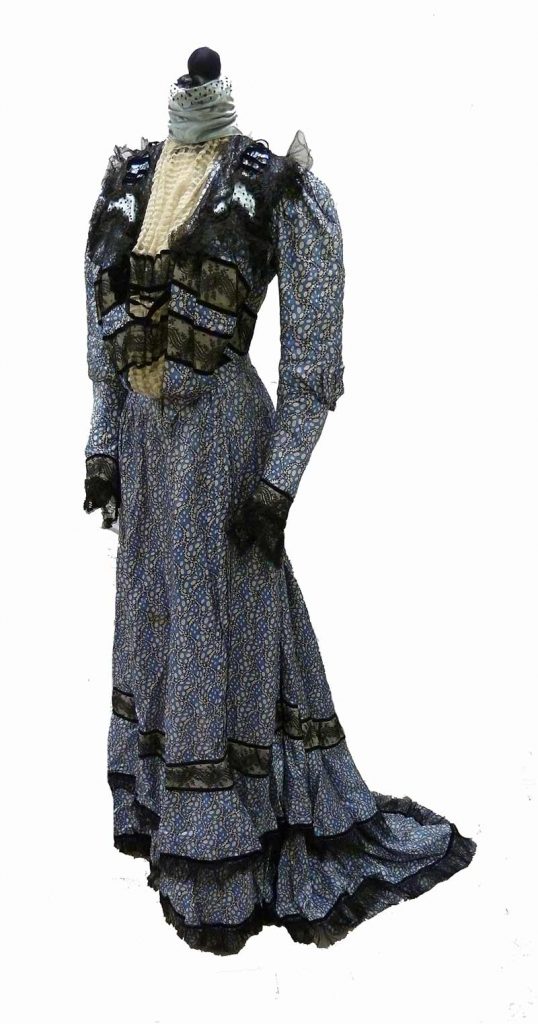

Silk and lace dress. ca 1900. Gift of A. Leonhard. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. This garment belonged to Emily Wells Grant (1857-1908), third wife of Heber J. Grant (1856-1945), the seventh and longest-tenured President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS.) She was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, a territory that passed legislation recognizing women’s voting rights in 1870.

Suffrage in Utah is a story of women gaining, losing and then regaining the vote. Religion played a major role in the fight for woman suffrage in Utah. Politicians hoped that recognizing women’s suffrage rights would aid in ending polygamy, a frequent marital practice of Mormons. However, Utah women did not necessarily vote for candidates opposed to polygamy as was the hope of anti-polygamists; rather many women hoped to demonstrate that they had chosen the LDS church and practices willingly. As a result, voting rights were rescinded through the Edmunds-Tucker Anti-Polygamy Act in 1887. When the LDS church officially ended the practice in 1890, it opened the door for Utah to join the union in 1896, and voting rights for women were restored.

Women from the LDS Relief Society developed programs to educate women about their roles in civic engagement from the beginning. Many, including Emmeline B. Wells, were delegates at national suffrage conventions, and it was Wells who helped to lobby for the vote in 1895. Wells, a plural wife of Emily Wells Grant’s father, was a prominent voice for suffrage and advocate for women’s rights. Very early on, Utah women such as Wells were able to develop ties with leading suffragists like Susan B. Anthony. Indeed, Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton visited Utah in 1871 as observers of the “suffrage experiment.”

Suffrage: 1900s-1910s

“Fifty years ago my grandmother came before the Missouri legislature and asked for the enfranchisement of women; twenty-five years ago my mother came to make the same request; tonight I am asking for the ballot for women. Are you going to make it necessary for my daughter to appear in her turn?”

– Christine Orrick Fordyce, in address to the Missouri Legislature, Jefferson City (1917)

The torch for woman suffrage – both literal and figurative – was carried by a new generation of Missouri women in the new century. The suffragist’s arguments often resonated best in urban areas, but were less effective in states like Missouri, where farm women had different concerns. Continuing to argue that women should have a voice in the selection of those who were to govern and legislate for them, they launched grassroots campaigns, including parades, automobile tours, visits to county fairs and theatric tableaus, focusing on the concerns of farm women.

Suffrage organizations promoted equal suffrage using a variety of methods including picket lines, parades, speeches, and rallies. Courage, fortitude and dedication were necessary in the fight for woman suffrage as participants were often ridiculed, scorned, harassed, assaulted, and even jailed. In 1914 the Columbia Equal Suffrage League began house-to-house canvassing to promote and record sentiment on equal suffrage. That same year, a suffrage school was established at the University of Missouri, as well as the College Equal Suffrage Association, to generate interest by University women on the issues for woman suffrage. The most visible suffrage event in Missouri occurred on the opening day of the 1916 National Democratic Convention in St. Louis. A “walkless, talkless parade” of over 3,000 women was organized to demonstrate that without the right to vote, women’s voices were silenced. Wearing white and carrying gold parasols, it became known as the Golden Lane.

Board meeting of the Equal Suffrage League of St. Louis. 1912. Image courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, St. Louis, Missouri. A lecture by well-known English suffragette Ethel Arnold in St. Louis on April 10, 1910, inspired ten women to form the Equal Suffrage League of St. Louis. In February 1911, the Kansas City Woman Suffrage Association was formed. Later that spring, the leagues formally organized the Missouri Equal Suffrage Association. The following year, the League invited leading British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, one of the most influential organizers of the British suffrage movement, to St. Louis. Over the next several years, multiple regional and national suffrage conferences were held in St. Louis and Kansas City, bringing to the state national suffrage leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Rev. Dr. Anna Shaw.

Cotton shirtwaist. 1910s. Gift of B. Stone. Pleated wool skirt. 1910s. Gift of MU Theatre. Corn husk hat. 1910s. Gift of H. Jones. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri.

Clothing of the nineteenth century generally consisted of long, cumbersome skirts, multiple layers, and constricting corsets that hampered easy movement. During the early twentieth century, as women began leading more active lifestyles and seeking roles outside the home, shirtwaists and skirts, as well as tailored suits, afforded easier movement with fewer restriction. The overall trend was away from bulky layers and towards manageable, practical outfits. These styles quickly became associated with the period’s independent, educated, politically active “New Woman.”

Changing forms of women’s dress invoked and challenged popular perceptions of femininity. For leaders of the woman’s movement, the battle over women’s dress was a critical part of the battle for sexual equality and even the right to vote. Suffrage leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony forcefully defended a woman’s right to dress as she pleased. “Why, pray tell me, hasn’t a woman as much right to dress to suit herself as a man?” Anthony asked a reporter in 1895. “[T]he stand she is taking in the matter of dress is no small indication that she has realized that she has an equal right with a man to control her own movements.” (Lynn Sherr, Failure is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words (Times Books, 1995), p. 196.) “The First New Woman,” The Washington Post, August 11, 1895, page 20.

Gordon Grant (1875-1962) Which? Ink and graphite on paperboard. Published in American Puck magazine, June 5, 1912. State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri. Depicts a young woman in graduation robes seemingly choosing between joining the Women’s Suffrage Movement and a man proposing marriage. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Peter Mayo.

Wool suit. Mid-1910s. Gift of F. Maupin. Grass hat. 1920s. Gift of R. Tofle. Reproduction sash. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri.

Suffragists used dress as a powerful form of communication, although they were not always in agreement. But, to avoid accusations of eccentricity, over-focus on high fashion, or of “mannish” dress, all of which could harm their cause, women dressed in their smartest clothes: tailored suits, crisp white shirts, stylish hats. Suits were required for every woman’s wardrobe, worn for almost any daytime event. In the early teens, suits featured longer jackets and narrower skirts that began to reveal the ankle which had to be covered by boots in daytime.

Suffragists often wore long white dresses, associated with purity, which also made for better visibility with the color of sashes or other regalia. Though sometimes depicted in masculine dress such as pants or bloomers, suffragists realized early on that such a radical choice would draw attention away from their cause. Some did adopt traditional yet highly visible dress, such as Susan B. Anthony’s signature red shawl.

Missouri Ladies Military Band from Maryville marches in woman suffrage parade, Washington DC. March 3, 1913. Photograph. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. In late January 1913, Alma Nash, director of the Missouri Ladies Military Band of Maryville, Missouri, received notification from the National Equal Suffrage Association that they were selected as the only all-female group of musicians to march in Washington DC’s first women’s suffrage parade on March 3, 1913.

Black suffrage groups also participated in the march but were forced to the back of the procession. A crowd of 5,000 people, the largest of its kind in the U.S. at the time, gathered along the parade’s route, most in attendance for Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration the next day. Anti-suffrage forces within the crowd disrupted the parade, surging into the street and subjecting the marchers to spitting, taunting and harassment. Between 100 and 300 people were injured in the mob. In order to continue the procession, the Missouri band was thrust to the forefront to lead the parade through the crowds. Soldiers from nearby Fort Myer eventually arrived to restore order.

Wool band uniform worn by member of Missouri Ladies Military Band. 1913. Nodaway County Historical Society, Maryville, Missouri.

“We did not have time to stop and think about the really important thing we did when our band led the parade down Pennsylvania Avenue.” Alma Nash [Director] said on her return to Maryville. “We were not right in the lead when the parade started: a number of women escorts, a number of walking officers of the National Equal Suffrage Association, with our band following, was the order when we first started. We had gone but a short distance when the crowd started closing up toward the line of the parade, and men blockaded a place in the street a short distance ahead. One of the suffrage officers came rushing back to us and told us to march on ahead and lead; that it would be necessary for the band to open the way proved true. We were not molested in the least and although the march was slow on account of the crowds, no one offered to stand in our way down the avenue.” “Alma Nash and Her Band,” Missouri Women: Women of the Past, Inspiring Women Today. November 16, 2010. Original post by Melissa Middleswart and Meghaan Binkley of the Nodaway County Historical Society.

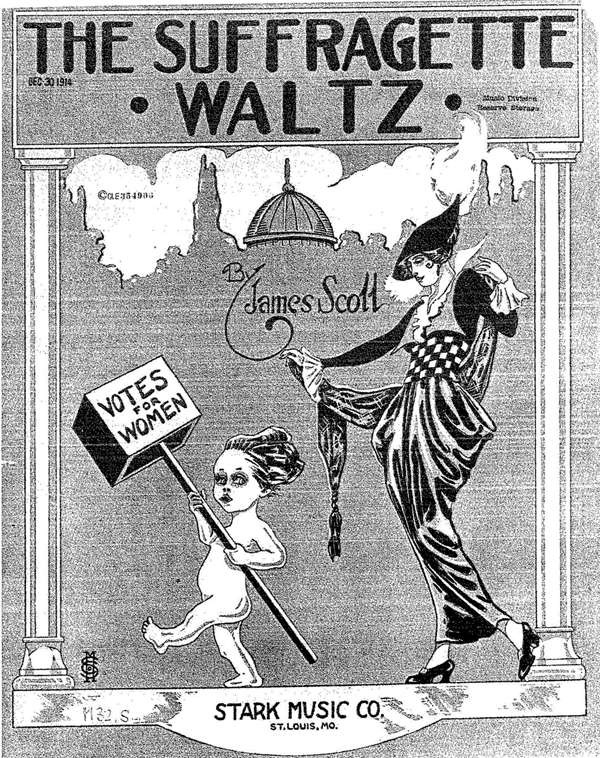

James Scott (1885-1938). The Suffragette Waltz. Stark Music Company Catalogue, December 30, 1914. Paper. Considered one of the top ragtime composers of all time, African-American composer and pianist James Scott was born in Neosho, Missouri, to former slaves James and Molly Scott. Scott spent his teen years playing in bands and saloons. In 1905 Scott travelled to St. Louis in search of his idol, legendary ragtime composer Scott Joplin, who introduced Scott to his own publisher, John Stark of Stark Music Company. Listen to Scott’s waltz online.

The mostly white suffrage movement largely ignored the challenges faced by African American women and often discriminated against black women working towards the same goal. Black women as a whole were often excluded from conventions and forced to march separately in suffrage parades. As a result, black reformers began organizing their own groups in the 1880s. The significance of black women in the women’s suffrage movement was also largely overlooked in the first suffrage histories.

Jane Addams, Portrait by the Gerard Sisters, St. Louis. 1914. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In 1914, Jane Addams, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, trailblazing social reformer, and future Nobel Peace Prize recipient, spent three days in Missouri promoting woman suffrage. On October 22nd, Addams visited Columbia at the invitation of the Columbia Equal Suffrage League and former MU President Richard Henry Jesse. Due to strong anti-suffrage sentiment, Addams was unable to speak in the University auditorium and instead spoke to an overflow crowd at Columbia Theatre and again at the Baptist Church.

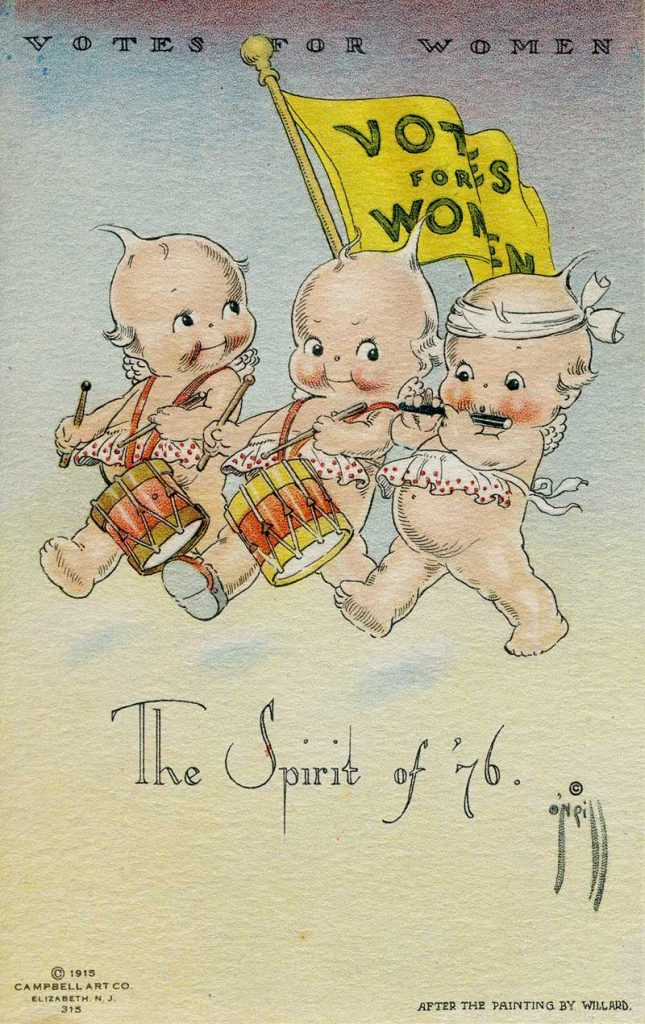

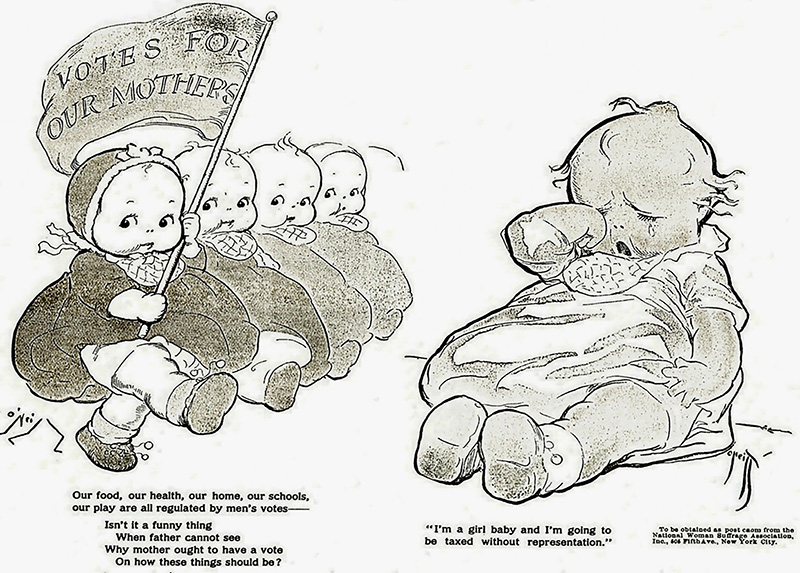

Rose O’Neill. Votes for Mother, The Spirit of ‘76. 1915. Paper postcard. Bonniebrook Historical Society, Walnut Shade, Missouri. American artist and writer Rose O’Neill became one of the highest paid illustrators – male or female – of the early 20th century, due in part to the creation of one her most well- known characters, the Kewpie. O’Neill designed the cherubic winged Kewpie in 1909 while residing at Bonniebrook, her family homestead near Branson, Missouri. “I say this is not a doll, but a message of good will sent forth to cuddle the hearts of the uncuddled world.”

Beginning in 1912, Kewpies were mass-manufactured in porcelain, celluloid, chocolate, and wood. Kewpies featured prominently in the woman suffrage campaign. Beginning in 1915, while living with her sister, Callista in New York, O’Neill became involved with the women’s suffrage movement. She marched in parades, gave speeches, and illustrated posters and postcards for the movement.

Celluloid Kewpie doll by Rose O’Neill. 1914. Image courtesy of D. Davis. In 1914 Kewpies were used as a public relations stunt during the National American Woman Suffrage Association Convention in Nashville, Tennessee. The pioneering aviator Katherine Stinson swept her airplane over the heads of the assembled crowd to release a shower of 4″ celluloid Kewpie dolls swathed in yellow suffrage sashes and tiny yellow parachutes. In 1916, Mrs. John Blair, with pilot Leda Richberg-Hornsby, dropped suffrage leaflets on President Wilson while he was aboard his Presidential Yacht.

Rose O’Neill. Baby Taxed Without Representation: Votes for Mother. 1915. Paper poster. Image courtesy of Bonniebrook Historical Society, Walnut Shade, Missouri. Artist Rose O’Neill’s Kewpies featured prominently in the woman suffrage campaign. One of her more strident statements in support of suffrage appeared in the New York Times on April 14, 1915: “Man has made and ignorantly kept woman a slave. He has forced upon her certain virtues which have been convenient to him. He has damned as intuition her greatest virtue: knowledge.”

Suffragists of the St. Louis Equal Suffrage League on their way to travel across Missouri to promote woman suffrage. 1916. Image courtesy of Missouri History Museum, St. Louis, Missouri. By the 1910s, after decades of fighting for the vote, many women decided that the best way to promote the cause and to reach rural populations was to travel. This included automobile tours of smaller communities. National speakers as well as local organizers adopted new tactics that took them not only door-to-door but also to county fairs and regional events held by organizations like the Farmers’ Alliance and the Grange. In 1913, suffragists from all 48 states drove across the country to secure signatures on petitions that called for a suffrage amendment. This was not an easy feat given that few roads were paved, or at best paved with gravel. Many women traveled by train, while others set out on walking pilgrimages, making speeches and giving interviews. In 1916, a “Suffrage Special” train tour set out to recruit supporters from the western states where women were already enfranchised to campaign for national suffrage.

Rev. Dr. Anna Shaw of NAWSA embarking from train, St. Louis, Missouri. 1916. Image courtesy of Missouri History Museum. Suffragists campaigned for women’s suffrage throughout the state of Missouri, walking door to door and travelling by train and automobile. Suit separates and shirt waists with skirts enabled more freedom of movement and made for more comfortable travel. Fur accessories like the stole and muff on display were frequently used to keep warm during cold days of picketing, speeches and travel.

Navy wool suit. 1910s. Gift of M. Rickmeyer. Silk velvet hat. 1910s. Gift of M. Happel. Fur stole. 1955. Gift of S. Bingaman. Fur ruff. 1890s-1910s. Gift of H. Natsch. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri.

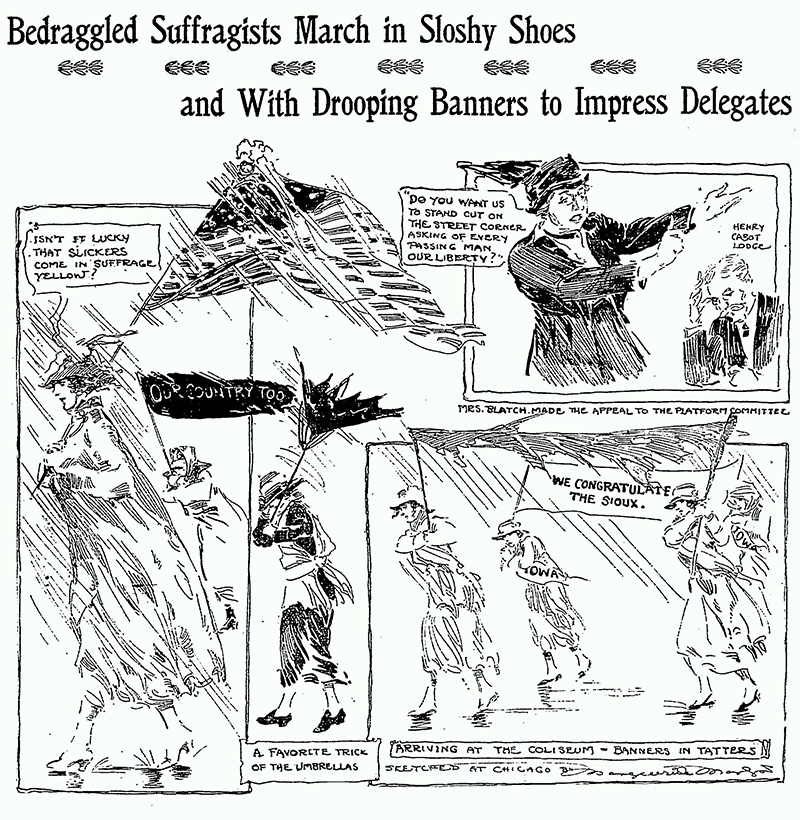

Martyn, Marguerite. “Bedraggled Suffragists March in Sloshy Shoes…” June 8, 1916. Image courtesy of the St. Louis Post Dispatch, Proquest Historical Newspapers.

Linen duster. 1910s. Gift of B. Stone. Wool suit. 1900s. Gift of R. Tofle. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection.

Suffragists travelled throughout the state to promote woman suffrage, by foot, train and automobile. In the early years of the automobile, driving and riding in open cars required protective outerwear from flying dust and mud. Early “motoring dress” included goggles, gloves, a scarf, hat with veil, and either a long heavy coat for winter or lightweight “duster” coat for warm summer months.

Sports motorist Dorothy Levitt – one of the first British female racing drivers and author of the 1909 handbook The Woman and the Car : A Chatty Little Handbook for All Women Who Motor or Want to Motor – provided useful tips for women drivers on what to wear. If driving in an open car, “neatness and comfort are essential.” On choosing the right dress, she wrote “Under no circumstance wear lace or fluffy adjuncts to your toilette – if you do, you will regret them before you have driven half a dozen miles.” She also recommended women wear a round cap or “close-fitting turban of fur” that fit well, and to tie a veil over it in order to protect the hair and keep the hat in place. A scarf and gloves were also useful. The glove compartment was to be stocked with a list of indispensable items: “a pair of clean gloves, an extra handkerchief, a clean veil, powder-puff, hair-pins, a hand mirror – and some chocolates are very soothing, sometimes!” Levitt, Dorothy. The Woman and the Car. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head; New York: John Lane Company (1909).

Male delegates to the Democratic National Convention in St. Louis, Missouri walk along the Golden Lane. June 14, 1916. Image courtesy of Bryn Mawr College Library, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. The most visible suffrage event in Missouri occurred on the opening day of the 1916 National Democratic Convention in St. Louis. A Golden Lane, also known as the “Walkless, Talkless Parade,” was formed on both sides of Locust Street, along the delegates’ walking path from their hotel to the nearby St. Louis Coliseum. Over 3,000 women lined twelve blocks dressed in white, wearing yellow sashes and carrying yellow umbrellas. The silent event was to demonstrate that without the right to vote, women’s voices were silenced. Present at the day’s events were Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association with Rev. Dr. Anna Shaw, honorary president.

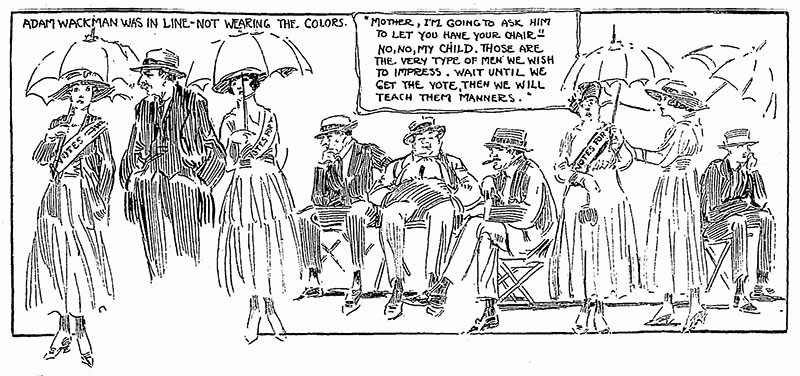

Marguerite Martyn (1878-1948) Men Took Women’s Chairs and Crowded Them Out of Their Places in “Golden Lane” of Suffragist “Walkless Parade.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. June 15, 1916. Image courtesy of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Proquest Historical Newspapers. The Golden Lane was covered by St. Louis Post-Dispatch journalist and illustrator Marguerite Martyn, a student of Washington University’s School of Art in St. Louis. One of few women employed by newspapers at the time, Martyn chronicled several interactions she observed for the next day’s newspaper.

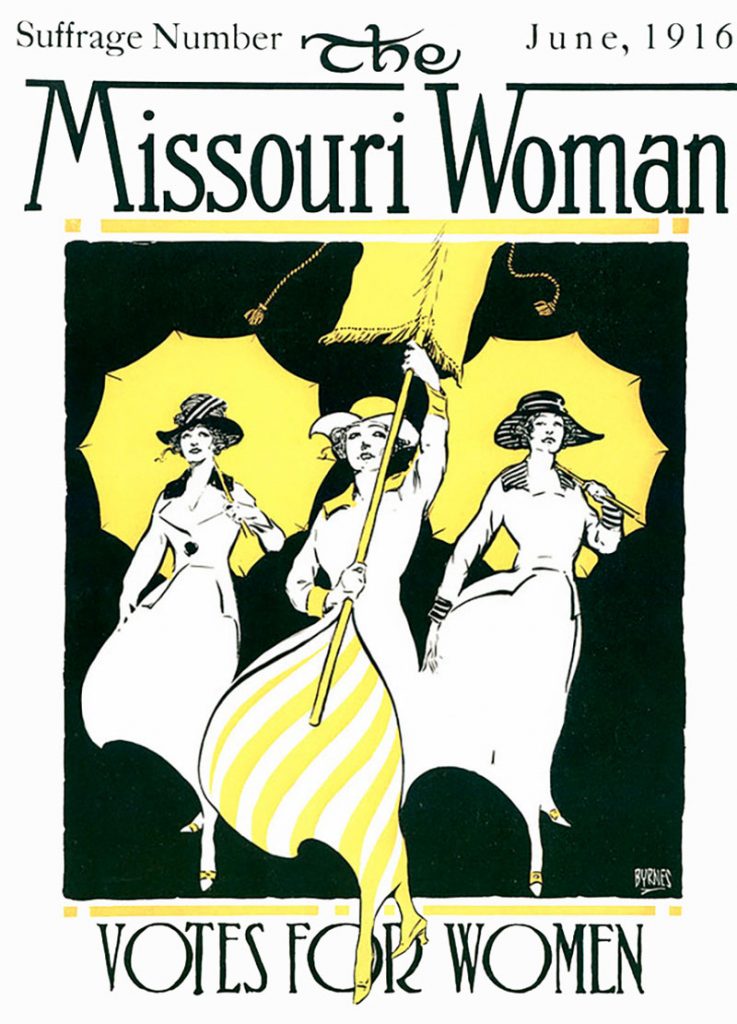

By 1913, leading daily and weekly newspapers in St. Louis and Kansas City gave their support to the suffrage movement. Ardent suffragist Flint Garrison, president of the Garrison-Wagner Printing Company of St. Louis, saw the possibilities of a monthly suffrage magazine, and began publishing the Missouri Woman in December 1915 with Emily Newell Blair as editor. Circulation increased following endorsements by prominent women’s groups such as the Missouri Federation of Women’s Clubs, the National Congress of Mothers,’ and the Parent-Teachers’ Association.

The June 1916 issue was created to impress the public in anticipation of the Golden Lane event to be held at the National Democratic Convention in St. Louis. William Byrnes, a well-known artist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, designed the cover featuring suffragists in white dresses carrying golden parasols and banners. The Missouri Woman generated significant sentiment for woman suffrage throughout the state. Its mission became less critical, however, after ratification of the Federal Suffrage Amendment in 1920. The following year, the St. Louis publication merged with The Woman Citizen, one of the most influential women’s publications of the early 20th century.

Recreation of Golden Lane. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. The silent protest of the 1916 Golden Lane at the National Democratic Convention in St. Louis was successful, as Democrats at the convention agreed to endorse the enfranchisement of women and urged states to adopt it. When the roll call vote began and it became clear the suffrage plank would pass, “one yellow parasol began to wave, then more and more of them were unfurled. The Coliseum looked as if a field of golden California poppies had suddenly sprung up,” wrote Bertha K. Passmore, Vice chair of the Missouri Equal Suffrage Association.

College Day on the Picket Line, Washington, DC. February 3, 1917. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Hazel Hunkins (pictured second from left wearing a University of Missouri sash) was a Chemistry professor at the University of Missouri from 1913 to 1916 while also seeking a masters degree. In 1916, she went to California as part of the aviation corps of the suffrage army. Later that same year she travelled to Colorado as the Montana state chairman of the National Woman’s Party to help launch their national campaign. Her first suffrage march was in 1917 in Washington, DC., during which men jeered and spat at the marchers, slapping at them and tearing their clothes. On January 10, 1917, the National Woman’s Party began posting “Silent Sentinels” – a silent picketing brigade – in front of the White House in Washington, D.C. Suffragists stood silently in all kinds of weather, six days per week for an entire year, enduring a variety of verbal and physical abuse from bystanders. As part of the Silent Sentinels, Hunkins chained herself to the White House gates and set fire to the White House lawn.

“We are going to start picketing again and no one knows how I hate it. Oh how I hate it. But somehow I can’t say no when everybody else is doing it and it is just as much of a burden to them as it is to me. But how I hate it. I am heart and soul with the idea [of picketing]. It’s just the physical torture that I hate.”

– Hazel Hunkins, Letter to Mother. March 30, 1917. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society and the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute

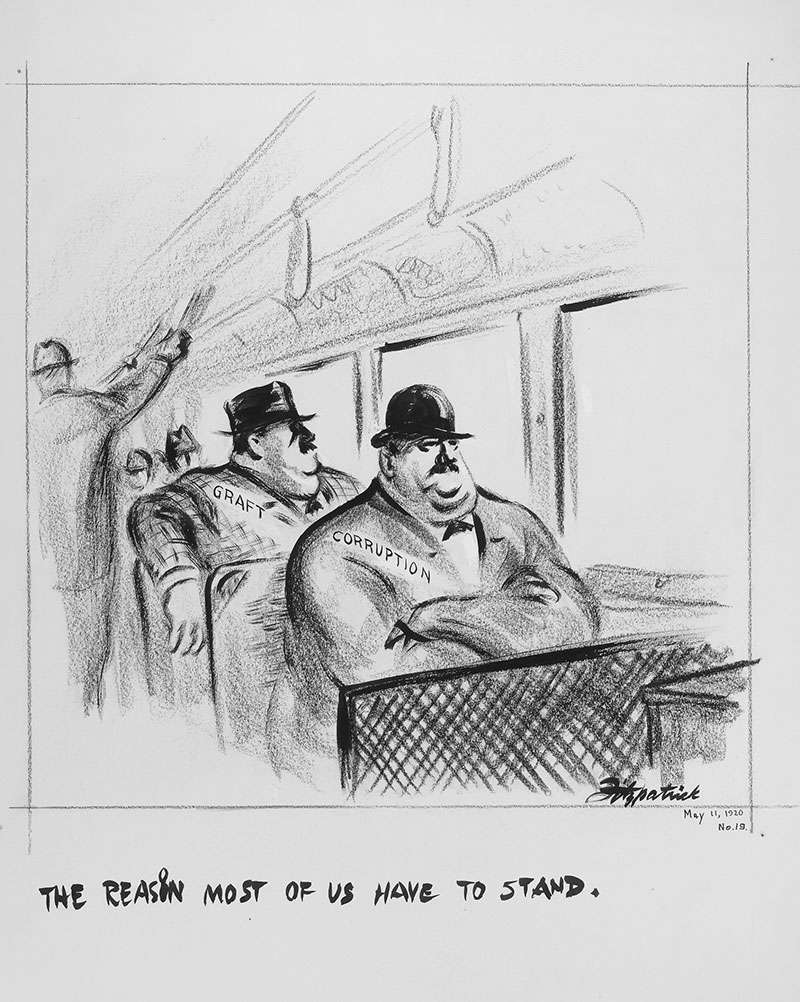

Daniel Fitzpatrick (1891-1969) Why the Rest of Us Have to Stand. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 11, 1920. Courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri. Crayon, ink with pen and brush. Gift of the artist. Daniel Fitzpatrick, a two-time-Pulitzer-Prize-winning cartoonist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, was well known for his evocative caricatures of politicians and corrupt business men. This cartoon from the suffrage era presents stereotypical figures of shady politicos from the 1910s and 1920s. In this particular image, the figures embody concepts of “corruption” and “graft,” but one can also see in them the kind of sexist characters suffragette Hazel Hunkins described in a letter to her mother written on March 3, 1917; see next image.

“If there is anything that can make me boil, it is to be told by some great big fat pompous slobby dirty dishonest politician that women weren’t capable of voting correctly and in the same breath say with a smirk that he’d do anything for the ladies. And to think that he has the power to decide on this question!”

– Hazel Hunkins, Letter to Mother. March 30, 1917. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society and the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute

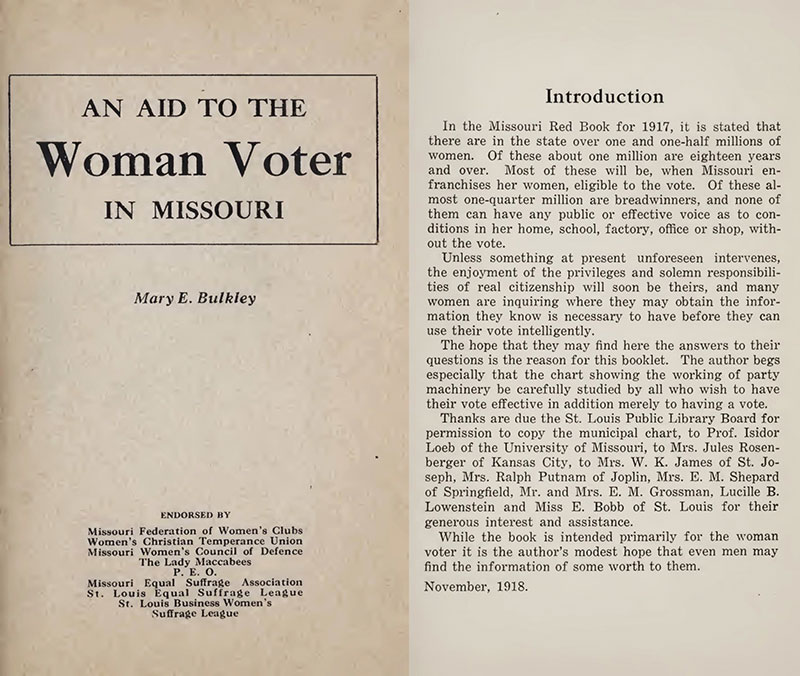

Mary E. Bulkley. An Aid to the Woman Voter in Missouri. November 1918. Title Page and Introduction. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. A prominent member of the St. Louis Equal Suffrage League and the Missouri Equal Suffrage Association, Mary Bulkley helped establish, and served as contributing editor, for the monthly suffragist magazine The Missouri Woman, published in St. Louis by the Garrison-Wagner Printing Company. In 1918 Bulkley wrote An Aid to the Woman Voter in Missouri as a guide to help women “use their vote intelligently.” The guide explained political parties, the process of voting, and the organization of city, state, and federal governments. It was used to outline lectures in government for Citizenship Schools throughout the state.

Opposition to Woman Suffrage

“We oppose woman suffrage because… the basis of government is physical force. It isn’t law but law-enforcement, which protects society. Woman could not enforce the laws even if she made them.”

– From paper flyer titled We Oppose Woman Suffrage printed by the Woman Anti-Suffrage Association of New York. ca. 1916.

There were always those opposed to woman suffrage. Opponents of woman’s suffrage formed regional groups as early as the 1860s, first in Massachusetts where some of the early suffragists lived. An organized national anti-suffrage movement did not begin to form in the U.S., however, until the end of the nineteenth century. And while men were involved in the anti-suffrage movement, most groups were led by women. The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) was founded in 1911 by Josephine Dodge. Dodge had also led a movement to assist working mothers by founding day care centers, a philosophy that fit with the anti-suffragist argument that women should be taking care of their home and their children. Many also thought that women did not belong in the “dirty” world of politics. Suffrage especially frightened industrialists and distillers who were concerned about the potential for women to be reformers.

Flier titled “We Oppose Woman Suffrage.” ca 1916. Paper flier printed by the Woman Anti-Suffrage Association of New York. Image courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, St. Louis, Missouri. Those who opposed woman suffrage had various reasons for their beliefs. Many thought that women did not belong in the “dirty” world of politics. Suffrage especially frightened industrialists and distillers who were concerned about the potential for women to be reformers.

Marguerite Martyn. “Men Took Women’s Chairs…,” detail. June 15, 1916. Courtesy of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Many opposed to woman suffrage believed there was a natural order that required men and women to operate in separate “spheres.” According to a 1915 Anti-Suffrage brochure: “Woman Suffrage, by introducing a new element of discord into the family, tends to increase material infelicity and consequent divorce.”

As part of the natural order, women cared for home and family. Who would manage these tasks if not women? At the 1916 Democratic National Convention in St. Louis, a Michigan delegate, commenting on the suffragists’ Golden Lane, argued, “…I’d just like to know who is at home taking care of the babies.”

Ruf Nex. MU Savitar. 1920, page 326. Courtesy of University Archives, University of Missouri. The southern states often actively opposed woman suffrage as a reflection of tensions about citizen-ship and race. Thus the fight for the vote was, in general, more divisive and challenging in the south. Southern women did however create branches of suffrage organizations such as the American Woman Suffrage Association. Passage of the 14th and 15th amendments was used to support the conversation about extending the vote to women. But links between woman suffrage and black voting rights served to put both into question. Anti-suffrage leaders were often from the wealthy planter class and feared racial disorder.

Ratification: 1920

“Last but far from least this stirring incident in the constitutional history of Missouri should be interesting to the heirs of those who won the heritage; the women who will profit from it. Counting their debt to those whose sacrifices made this victory possible, they will resolve by their type of citizenship to repay to the uttermost farthing.”

– Mrs. Emily Newell Blair, Missouri Historical Review, April-July 1920

From 1870 to 1920, women went to the Missouri State Legislature in Jefferson City every session to present their appeal for votes for women. Their efforts were rewarded in March 1919 when the Missouri General Assembly passed the Presidential Suffrage Bill (Bill #1). Missouri women could now vote for President and Vice-President in the upcoming November 1920 election.

Immediately following Missouri’s partial ratification, members of the Missouri delegation attended the Golden Jubilee Convention held by the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) the week of March 23-29 in St. Louis. This convention would be described by suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt as “the best convention ever held anywhere.”

“Suddenly music was heard from the back. It heralded the Missouri delegation just returned from Jefferson City with the joyful tidings that it had passed both Houses! The delegation was met at the door and escorted down the center aisle by Mrs. Edna Gellhorn, holding aloft a banner bearing the words, “Now we are voters.” The large audience rose spontaneously and, amidst deafening cheers and wild waving of handkerchiefs and hats, the women ascended to the stage, where they were individually presented to the audience by the presiding officer, Rev. Dr. Anna Shaw, who congratulated them and the rest of the women of Missouri on the great victory.”

– Votes for Women: Complete History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in U.S. by Jane Addams, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Ida Husted Harper, Anna Howard Shaw, Matilda Gage, Susan B. Anthony, Harriot Stanton Blatch, Alice Stone Blackwell; Madison & Adams Press, 1919.

On April 5, 1919, Missouri Governor Frederick D. Gardner signed the Presidential Suffrage Bill into law. On July 3, 1919, a special session was called to vote on the Suffrage Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, also known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. The 50th Missouri General Assembly passed the amendment by a vote of 125 to 4 in the House and 29 to 3 in the Senate. Missouri became the eleventh state to ratify the Suffrage Amendment. The first eleven states ratified the Amendment within a month. It would take another year for the thirty-sixth state to ratify and make it the 19th amendment of the U.S. Constitution in September 1920. Only a few days later, in a special election, women of Hannibal, Missouri voted for the first time.

Pen used by Missouri Governor Gardner to sign the Presidential Suffrage Bill. April 5, 1919. State Historical Society of Missouri. After the Missouri General Assembly failed to pass two women’s suffrage bills in 1917, Governor Gardner called on the 50th General Assembly to extend women the right to vote. On April 5, 1919, Gardner signed Senate Bill 1, the first bill passed in the new state capitol building, guaranteeing women Missouri women the right to vote for president and vice-president of the United States. This enabled women to register and vote in the upcoming presidential election in November 1919. The complete inscription on the pen reads, “PEN USED BY GOVERNOR FREDERICK D. GARDNER IN SIGNING THE BILL GRANTING PRESIDENTIAL SUFFRAGE TO MISSOURI WOMEN APRIL 5 – 1919.” The ferrule is significantly tarnished, but one can still see ink dried on the pen nib, perhaps from when the bill was signed.

Missouri Governor Frederick D. Gardner ratifies the Suffrage Bill in Jefferson City, Missouri. July 3,1919. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Edna Gellhorn, leading Missouri suffragist and first vice-president of the newly-formed League of Women Voters, stands to the Governor’s left with her hand on Gardner’s chair.

League of Women Voters rally and parade, St. Louis, Missouri. September 13, 1920. Image courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, St. Louis, Missouri. The first day women could register to vote was September 13, 1920. For days prior, Edna Gellhorn, first national vice-president of the newly formed League of Women Voters, had traveled all over the state to talk to women about how important it was to get out and register. On the first day of registration, Gellhorn organized a voter registration rally and parade in downtown St. Louis to inform as many women as possible of their ability to vote. Her efforts paid off. Between September 13 and September 16, over 125,000 women registered to vote in St. Louis, more than doubling city officials’ projections.

Wool suit. 1910s. Gift of MU Theatre. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. A popular suit style into the early 1920s, this black suit and shirtwaist are similar to those worn during the St. Louis registration rally and parade from September 13-16, 1920, when over 125,000 people registered to vote, many of them women who registered for the first time.

A Woman Living Here Has Registered to Vote Thereby Assuming Responsibility of Citizenship. 1920. Paper window flier. Image courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, St. Louis, Missouri. Just as today’s voters receive a sticker bearing the words “I Voted,” those who registered in St. Louis on September 13-16, 1920, received a paper flyer for their windows at home as evidence they registered for the presidential election that year.

One of those individuals was Mrs. Ebbie Tolbert, a slave under five owners before escaping from Mississippi to Missouri. On September 14, 1920, Tolbert became the first African American woman in St. Louis to register to vote. At the age of 113, Tolbert walked down to her polling place in St. Louis, Second Precinct, Seventh Ward, and entered her name into the lists as a registered voter. The following day, an interview with Mrs. Tolbert appeared in the St. Louis Star and Times. Mrs. Tolbert said, “It is going to be a great honor to be permitted to vote,” and [she] believes if women will vote right, they can do much to improve the present laws. “The world isn’t like it used be,” said Ebbie Tolbert, “and it may take the women to make things better. “From the St. Louis Star and Times, September 15, 1920, page 3.

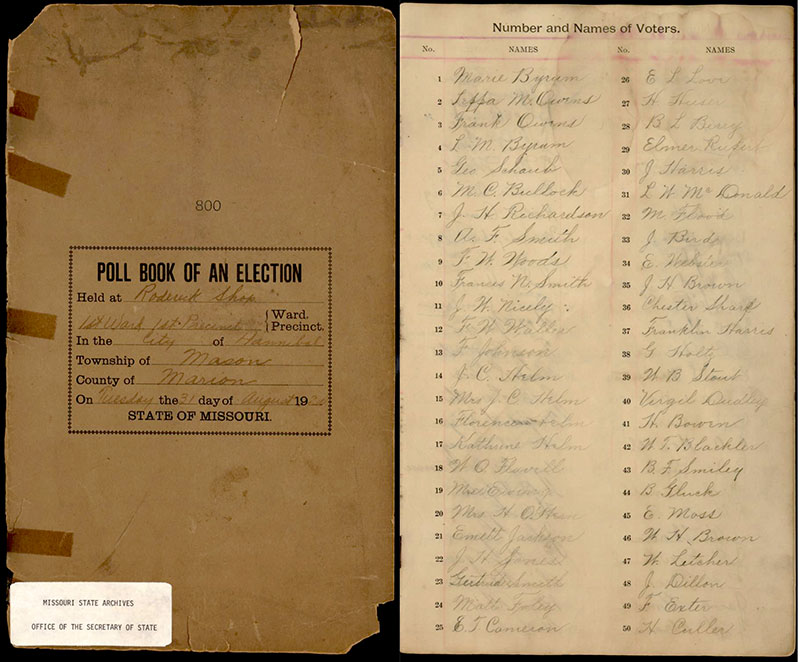

Poll Book of An Election, Hannibal, Missouri. August 31, 1920. Image courtesy of Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City, Missouri. Page 4, Line 1 contains the signature of Marie Ruoff Byrum, who, at the age of 26, the first woman to vote in Missouri and in the United States for her choice of a candidate for public office in a special election held just five days after ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Page 7 of the book includes the signature of Harriett Hampton, likely the first African American woman to vote in Missouri.

Trailblazing Missouri Women

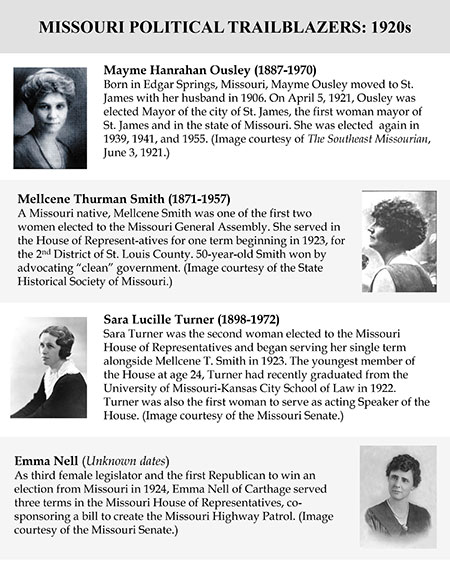

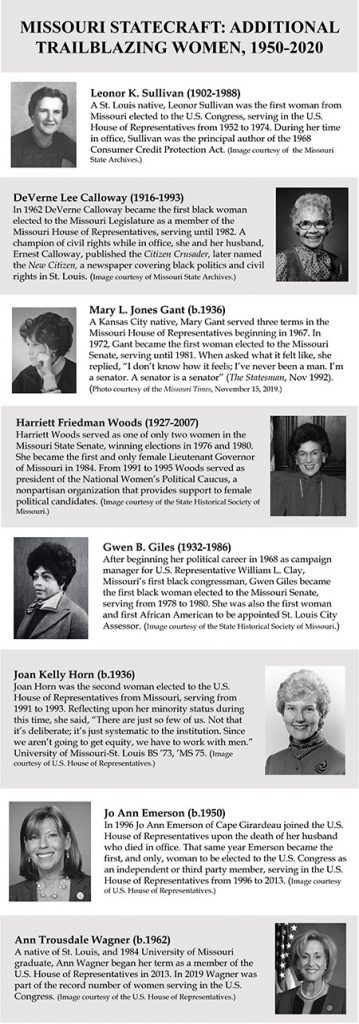

After women won the right to vote with the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920, many Missouri women aspired to participate as fully as possible in their own governance. Just as the earlier fight for equal suffrage challenged women of the 19th and 20th centuries, subsequent statecraft proved a challenge for those women who placed their names on the ballots. The all-male Missouri General Assembly slowly gained women representatives.

The first woman elected to public office in Missouri was Anna “Annie” White Baxter, as one of the nation’s first female county clerks, in 1890. In 1921, Mayme Ousley was the first woman elected mayor in Missouri (St. James). Other female mayors followed in 1924, 1936, 1977, 1989 (Columbia), 1999, 2015, 2017, and 2018. The all-male Missouri General Assembly slowly gained women representatives beginning in 1923. The first African-American woman would not be elected to the Missouri Legislature for another 40 years.

From 1980 to 1990 the percentage of women in the Missouri General Assembly grew from roughly 11 percent to 15 percent.

- 1963: DeVerne Calloway became the first black woman elected to the Missouri Legislature as a member of the Missouri House of Representatives.

- 1972: Mary Gant was the first woman elected to the Missouri Senate.

- 1977: Gwen Miles became the first black woman to serve in the Missouri Senate.

- 1989: Ann Covington was appointed the first woman on the Missouri Supreme Court.

- 1992: Claire McCaskill became the first woman elected County Prosecutor for Jackson County.

- 1996: Jo Ann Emerson remains the first and only woman to be elected and serve in the U.S. House of Representatives as an independent or third party.

Despite significant progress, the number of women to hold public office in Missouri remains a fraction of that of men. Women broke new records in 2018 primaries when 103 women ran for federal and state office. In 2019 women made up 24.6 percent of the Missouri legislator; forty-nine women out a total 197 positions, falling below the record nationwide average of 28.9 percent.

Former Lieutenant Governor Harriet Woods (1984-86) remains the highest ranking woman to hold office in Missouri, and the first woman elected to statewide office in Missouri. In its 199 years of statehood, Missouri has yet to elect a female Governor; however, the 2020 race for Missouri governor currently includes a female candidate. The torch for women’s equality remains lit for future generations.

Black polyester jacket and skirt. Late 1990s-2001. Portrait image: Chief Justice Ann Covington, 1993-95. Gifts of Ann Covington (b.1942-) Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. Ann Covington began her trailblazing law career as one of a small handful of women in the University of Missouri’s School of Law, graduating with her JD in 1977. In 1987 Covington became the first woman on the Missouri Court of Appeals, Western District. In 1989, Ann Covington became the first woman on the Missouri Supreme Court, and remained the only woman while serving on the Court until 2001. She also served as the first woman chief justice from 1993 to 1995. Covington recalls feeling “invisible” as the Court’s first and only woman, and carefully considered her dress and behavior to help ensure she would not be the last. This included dressing in styles similar to those worn by her male counterparts: sedate suit jackets and skirts rather than pants, as dresses were not considered professional attire as a member of the Supreme Court.

Portrait image: Mary Anne McCollum. 1988-89. Courtesy of the donor. Korean silk hanbok. 1991. Gift of Mary Anne McCollum. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. Mary Anne McCollum began her political career in Columbia on a stormwater task force. This was followed by terms on the Columbia City Council. In 1989 McCollum was elected Mayor of Columbia and served as the first – and only – female mayor until 1994. During her time in office, McCollum was part of the group that founded REDI (Regional Economic Development Inc.) and the Columbia Values Diversity breakfast. In 1991 she established a Sister City Relation with Suncheon, South Korea. The wife of Suncheon’s mayor gifted McCollum with this custom, hand-painted hanbok, made by one of the city’s top seamstresses. McCollum wore the hanbok at the Korean reception in 1992.

Blue bouclé suit jacket. Worn by Jean Carnahan as U.S. Senator from 2000-2002. Gift of Jean Carnahan (b.1933-) Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. Portrait image courtesy of U.S. Congress. The first of her family to graduate high school and college, Jean Carnahan was politically active while raising a family in Rolla, Missouri. She became First Lady of Missouri alongside her husband, Governor Mel Carnahan, in 1993. In 2000 Jean Carnahan was appointed U.S. Senator upon the sudden death of her husband, becoming the first woman from Missouri to hold that distinction.

Jacket and skirt, Label: St. John Knit. 2007-2019. Gift of Claire McCaskill (b. 1953-) Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. Portrait image courtesy of U.S. Congress. A native of Rolla, Missouri, Claire McCaskill served as Missouri State Representative (1982-1988), first female prosecutor for Jackson County, Missouri (1992-1998), and Missouri State Auditor (1998-2006.) In 2006, McCaskill became the first and only woman elected to the U.S. Senate from Missouri, serving from 2007 to 2019. She wore the aqua suit many times while visiting the White House and on the Senate floor. She graduated from University of Missouri, School of Law in 1975.

Polyester, rayon and spandex jacket and skirt; Label: Ann Taylor. 2009. Modified campaign flyer. 2009. Gifts of Vicky Hartzler. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. Vicky Hartzler earned a BS degree from the University of Missouri in 1983 followed by an MS degree from the University of Central Missouri in 1992. She ran for State Representative in 1994 and became a member of the U.S. House of Representatives in 2009. Congresswoman Hartzler was part of the record number of women in Congress in 2019. She describes this burgundy suit as her “signature suit” as it inspired the color scheme of her first campaign for U.S. Congress in 2009 which she still uses today.

Susan Vale. A Statement in Pink – National Mall – January 21, 2017. 2017. Acrylic on canvas. Gift of the artist. State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri.

Acrylic pussycat hat. 2017. Gift of K. Wood. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. The first Women’s March, a worldwide event, was planned for January 21, 2017 with the goal to advocate for human rights – including women’s right, healthcare reform, and worker’s rights. Worldwide participation in the first marches was estimated at over 7 million. In connection with the march, The Pussyhat Project was a nationwide effort initiated by Krista Suh and Jayna Zweiman to create pink “pussyhats” to be worn at the marches. Launched in November 2016, the project quickly became popular. The hat pattern was developed with Kat Coyle, owner of “The Little Knittery,” and had over 100,000 downloads. The concept was to create a “sea of pink,” a color traditionally associated with girls and women, to demonstrate solidarity for women’s rights, and to protest against the language used toward women and minorities in the 2016 election.

Ella Jones Portrait. Courtesy of the City of Ferguson. Autographed Cotton Campaign T-Shirt. 2020. Gift of Ella Jones. Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection, University of Missouri. Mayor Ella Jones was elected as Ferguson’s first Black and female mayor in June 2020. She was one of several Black female first-time mayors elected across the country this past June. A Ferguson resident for over forty years, Jones graduated from the University of Missouri at St. Louis with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Chemistry. In 2015 Jones became the first African American on the Ferguson City Council, a year after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by Ferguson police, an event that sparked nationwide protests. The event and subsequent unrest throughout the state and the nation influenced Jones’s decision to run for public office. (Left image courtesy of the City of Ferguson.)

Press

Radio Friends with Paul Pepper

Columbia Missourian