Originate, Adapt, Copy: Design Protection in the US Apparel Industry (2017)

The U.S. fashion industry produces clothing that is a complicated blend of original ideas, adaptations, and copies. Called design piracy by some and the “knock-off” process by most in the industry, copying fashion has been a firmly embedded business practice even prior to the advent of ready-to-wear. There have always been arguments both for and against the process of copying apparel. Historically, some industry organizations and individual designers accepted and supported the practice as important to the transmission of fashion, while others actively tried to prevent copying, stating reasons ranging from loss of profits to the potential for unfair labor practices.

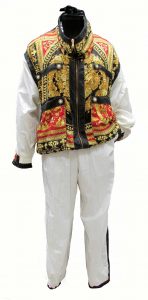

This exhibit displays objects that represent both originals, copies and adaptations, including a wool suit that had utility patent protection, a dress with protection from the FOGA, and illustrations from the Caroline G. Davis Style service, a company that made a living by selling copies of Paris designs as well as their own adaptations of those designs. In addition, some of the garments demonstrate the subtle nature of the copying and adaptation process, leaving the question open not only as to whether it is a copy, but indeed what represents original design.

Trademark

Trademarks – the names, signs, symbols, or devices attached to goods to identify their origin – tend to be the most recognizable representation of a brand. Internationally known trademarks within the apparel industry include the double “C” logo of Chanel, Louis Vuitton’s signature “LV” logo or Lacoste’s alligator logo. In the United States, trademark laws provide protection against counterfeiters, who copy the distinctive qualities of famous marks to create look-alike products and pass them off as the original. However, consumers often intentionally purchase copies of clothing and of pirated trademarked products such as handbags.

Click images to learn more. Historical and donor information will appear.

Copyright

Copyright laws generally give the owner the exclusive right to reproduce the work, to distribute copies and to display the work to the public. It is considered to include all types of creative work, including paintings, sculptures, films, books, etc. Copyright has never applied to apparel, however, because it is considered utilitarian, providing both protection and modesty, rather than being seen as art, with the exception of textile design and prints on textile, both of which can be copyrighted. In fact, most copying of apparel design is legal in the U.S. due to how intellectual property laws are written. Since 1914, nearly eighty bills to protect designs through copyright or to create a separate “design protection system” were introduced in Congress, the latest in 2012 when the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) sought legal remedies to curb piracy. This represented a renewed attempt at copyright legislation brought on, in part, by the increased competition from fast-fashion brands and retailers such as H&M, Zara, and Forever 21, companies that rely on knockoffs of higher-priced fashions. As an alternative to the failure of governmental protection, many have sought ways to protect their designs through industry organizations. Arguably the most successful of these was in the 1930s – the Fashion Originator’s Guild of America (FOGA). Read below to learn more about the FOGA.

Patents: Utility and Design

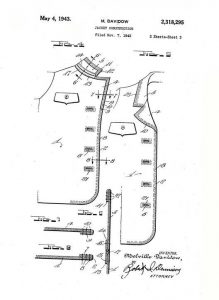

The patent system offers one possible avenue for design protection. Begun in 1970, patent laws confer “the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling” a unique invention. There are two types defined within the patent system – utility and design. Utility patents protect the way a machine, process or object works. Clothing that qualifies for a utility patent generally has an underlying technology that dictates function as well as appearance. The Davidow suit in the exhibit has a utility patent on the construction process used for finishing the edges of the jacket; see patent below. Design patents, on the other hand, protect intellectual property that falls between purely artistic works (covered by copyright) and inventions. Intended to protect the “ornamental” nature of a design, they were taken out in large numbers in the 1930s and 40s, and still are by some companies today. However, protection in the courts has been a challenge due to the need to demonstrate both novelty and the “inventive gift” of the designer.

Fashion Originators Guild of America (FOGA)

In the early 1930s, with the repeated failure of attempts at governmental protection, apparel industry groups formed to battle piracy through self-regulation. Maurice Rentner, manufacturer and designer of high-priced apparel, along with a group of other manufacturers of better dresses, founded the most successful of these industry groups, the Fashion Originators Group of America or FOGA. The FOGA sought to “cure the evil of design piracy” through retailer-manufacturer collaboration. It was initially quite successful (and controversial). However, by the mid to late 1930s it was continually brought to court as attempting to create a monopoly. The Federal Trade Commission issued the FOGA a “cease-and-desist” letter for ‘unfair methods of competition’. In a 1941 decision, the Supreme Court of the United States declared that the FOGA formed a monopoly and upheld the cease and desist order, declaring them “in restraint of trade” under the Sherman Act. Below are examples of MHCTC garments with FOGA labels.